A Failure of the Reformation

Scriptural Interpretation

By Dr. Andy Woods

Dr. Andy Woods is a native of California where he attended college and earned a law degree. In 1998 he shifted gears and started making the transition from law to theology when he decided to enter seminary.

He ultimately earned a doctorate degree in biblical exposition from Dallas Theological Seminary. He currently serves as pastor of Sugar Land Bible Church in the Houston area while serving as president of Chafer Theological Seminary in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He is a prolific writer and a much sought after conference speaker.

When the story of the Protestant Reformation is told, the subject must be approached with candor and intellectual honesty. The great contributions of the Protestant Reformers to the Christian faith notwithstanding, the Protestant Reformation really represented a mixed bag. As much as the Reformers are idolized today, their revolution can only be described as partial, at best.

One of the greatest contributions of the Protestant Reformation to Christianity involves the restoration of a lost method of biblical interpretation. While the Protestant Reformers selectively applied this method to some of the Bible, the complete revolution would have to await subsequent generations, who took the Reformers’ method of interpretation and applied it to the totality of God’s Word. The purpose of this article is to tell this other side of the story.

Scriptural Interpretation in the Early Church

Concerning Old Testament prophecy, even a casual perusal of the New Testament demonstrates that its biblical characters and writers interpreted these prophecies in a literal sense (Matthew 1:18–25; 21:12–13; John 12:12–15; Romans 11:25–27, etc.). Thus, it is not surprising to discover that Christianity’s second generation after the apostolic age also followed a literal approach when interpreting Bible prophecy.

In fact, what rose to prominence in early church history was the school at Syrian Antioch, which interpreted prophetic subjects in a literal manner. Accordingly, they taught that the kingdom of God would not materialize upon the earth until the King, Jesus Christ, first returns physically.

While this perspective is called Premillennialism today, it was known as Chiliasm then. This word, Chiliasm, comes from the Greek word, chilia, meaning “thousand” and is taken from the thousand year duration of Christ’s kingdom (usually referred to as the Millennium) which is referred to six times in Revelation 20:1–10.

The school at Antioch exercised such great influence over early Christianity, that virtually all of its most influential leaders were noted Chiliasts. In fact, in that day, one’s embracement of Chiliasm was viewed as a test to determine one’s orthodoxy.

Note the words of respected Church Father Justin Martyr (A.D. 100–160) in his Dialogue with Trypho: “But I and every other completely orthodox Christian feel certain that there will be a resurrection of the flesh, followed by a thousand years in the rebuilt, embellished and enlarged city of Jerusalem as was announced by the prophets Ezekiel, Isaiah, and the others.”

With such a well–entrenched belief within earliest Christianity concerning a literal interpretation of prophecy and a yet future earthly kingdom of Christ, when did the Christian world begin to shift on this vital issue of interpretation?

The Triumph of Spiritualization

The dominance of the Antioch school was soon eclipsed by the influence of a competing school located in North Africa in the city of Alexandria, Egypt.

The Alexandrian school introduced allegorization as a method for interpreting Scripture, especially Bible prophecy. Allegorization (or spiritualization) involves using the literal meaning of the biblical text only as a vehicle for introducing a higher spiritual meaning, which is only clear to the one doing the allegorizing.

For example, Philo (25 B.C.–A.D. 50), an influential allegorizer, who lived during the time of Christ, saw the four rivers depicted in Genesis 2:10–14 (the Pishon, Gihon, Euphrates and Tigris) as not just four literal rivers in the Garden of Eden but also representing four parts of the human soul!

What caused the Christian Church to progressively reject the traditional, literal approach as espoused by Antioch and instead embrace the allegorical method as outlined by Alexandria? At the risk of oversimplification, there were likely a multiplicity of factors involved.

First, the allegorical approach met the need for immediate relevance and application in Christian preaching and teaching. When the text is allegorized, it can be used to meet virtually any emotional, spiritual or psychological need in the listener or reader.

Second, the allegorical method became increasingly more tenable as Bible interpreters became susceptible to merging human philosophy into the process of biblical interpretation.

Third, a related influence was that Alexandria, Egypt was a hotbed for Gnostic dualism, which taught that while the spiritual world was inherently good, the physical world was evil. And since they believed that the physical world is inherently evil, Gnostic philosophers reasoned that the various biblical prophecies relating to a physical kingdom on earth were obviously not meant to be taken literally and that they therefore must be spiritualized.

A fourth factor leading the Church to embrace the allegorical method of interpretation was the decline in Jewish believers within the Church’s ranks. By the time Paul wrote his epistle to the Romans, the Gentile Christians were in such numerical ascendancy over their Jewish counterparts that Paul had to instruct these Gentile believers not to be arrogant on account of Israel’s apparent spiritual hardening (Romans 11:13,17–21).

Given the Jewish familiarity with not only the content but also with a proper understanding of Hebrew Bible, or the Old Testament, it is doubtful that the Church would have ever embraced the allegorical method of interpretation espoused by the Alexandrian school had the Jews retained their majority status within the Church. However, the Gentile Christians, coming out of pagan backgrounds, were not so similarly educated. Thus, they were vulnerable to the suggestion that the Old Testament could be spiritualized, allegorized and consequently marginalized.

Fifth, Constantine’s Edict of Milan (A.D. 313), which granted religious toleration to Christianity within the Roman Empire, also played a significant role in the Church’s embracement of the allegorical method of interpretation. With the stroke of a pen, Christianity went from a persecuted status within Rome to a protected and even elevated status.

Such an abrupt transition from persecution to tolerance and even elevation convinced many within the Church that the kingdom of God had now come. This newfound belief caused them to allegorize many of the terrestrial kingdom promises related to national Israel into present spiritual kingdom realities.

This convergence of factors led to the ascendancy of the Alexandrian method of interpretation within Christendom.

Prominent Allegorizers

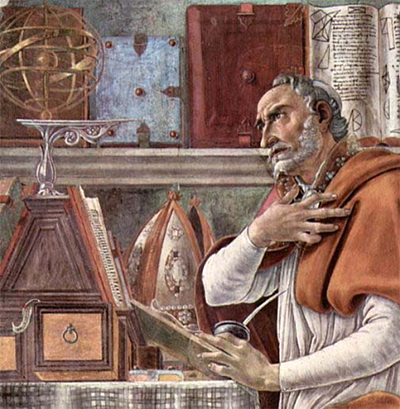

Several prominent allegorical interpreters arose out of the Alexandrian school. One such interpreter was Origen (A.D. 185– 254). But the most influential allegorizer was Augustine (A.D. 354–430). His book, The City of God, was the first major written systematization and exposition of Amillennialism in church history, and it is perhaps also the most influential book in church history. This work, more than any other, cast an allegorical spell over the Church which, as will be explained later, took Christendom well over a millennium to crawl out from under.

by Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510).

The City of God wildly allegorized the biblical passages dealing with the future earthly reign of Christ. For example, the “first resurrection” (Revelation 20:4–6) was reinterpreted to refer to spiritual regeneration rather than a future, physical, bodily resurrection. He also taught that the binding of Satan merely “means his being more unable to seduce the Church.”

Concerning the future thousand year reign of Christ along with His saints (Revelation 20:4), Augustine asserted that “the Church even now is the kingdom of Christ, and the kingdom of heaven. Accordingly, even now His saints reign with Him.”

By 450 A.D. the Alexandrian method of interpretation had become so entrenched that the Church began to view the earlier Chiliasm as the product of the less enlightened and less intelligent. In fact, Chiliasm itself began to be viewed as a mere fable rather than the product of a careful study of the biblical text.

The Dark Ages

The ascendency of the Alexandrian school plummeted the Church into a time often referred to as the Middle Ages or even “The Dark Ages.” During this era, the study of end time prophecy was rendered all but obsolete. This era dominated church history for well over a millennium. It lasted all the way from the 4th to the 16th Century.

During this era, only one church existed within Christendom, which was the Roman Catholic Church. Because of the dominance of the allegorical method of interpretation, only the clergy were deemed as qualified to read and allegorically interpret Scripture. Such a sharp clergy–laity distinction had the net effect of removing the Bible from the common man.

This problem was further compounded by the widespread illiteracy among the population, which made the Bible all the more inaccessible to the masses. To make matters worse, even up to the time of Luther, the Roman Catholic Mass continued to be read and conducted in Latin, although Latin was an unknown language to most people in Luther’s time. Thus, although many regularly went to Mass, they were unable to understand what was being communicated.

Such biblical illiteracy made the people vulnerable to spiritual deception and manipulation. The sale of indulgences was common throughout the era. The people did not have access to the Scripture to ascertain if Purgatory was even a biblical concept. Thus, the Church authorities routinely told them that they could purchase deceased relatives out of Purgatory by paying the right monetary sum to the Church. In fact, Johann Tetzel, a friar during the time of Martin Luther, infamously quipped, “When the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from Purgatory springs.”

The practice of the sale of indulgences was condoned by both the Church, as well as the existing political authorities, since they served as a convenient source of fund raising necessary to subsidize the Church’s various building projects, such as the refurbishment of Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

In addition, due to the inaccessibility to the Scripture, God’s future promises to the Jewish people were not available to serve as a natural defense or bulwark against the anti–Semitism of the day. Thus, rampant hatred of the Jews continued unabated and unchallenged. Due to these pitiful conditions, the Church was in dire need of theological rescue.

The Return to Literal Interpretation

The Protestant Reformation became the tool that God used to redirect the Church back to the solid foundation of His eternal Word. The Protestant Reformers rescued the Church from the Alexandrian allegorical method of interpretation through an application of a literal method of interpretation to selective areas of Scripture.

For example, William Tyndale (A.D. 1494–1536) asserted, “The Scripture hath but one sense, which is the literal sense.” Luther also wrote that the Scriptures “are to be retained in their simplest meaning ever possible, and to be understood in their grammatical and literal sense unless the context plainly forbids.” Calvin wrote in the preface of his commentary on Romans, “It is the first business of an interpreter to let the author say what he does say, instead of attributing to him what we think he ought to say.”

Because of their adherence to literal interpretation, both Calvin and Luther condemned the allegorical method of interpretation. Luther denounced the allegorical approach to Scripture in strong words. He said: “Allegories are empty speculations and as it were the scum of Holy Scripture.” “Origen’s allegories are not worth so much dirt.” “To allegorize is to juggle the Scripture.” “Allegorizing may degenerate into a mere monkey game.” “Allegories are awkward, absurd, inventive, obsolete, loose rags.”

Calvin similarly rejected allegorical interpretations. He called them “frivolous games” and accused Origen and other allegorists of “torturing Scripture, in every possible sense, from the true sense.”

The Reformers also did not want to see the biblical ignorance of the common man exploited for financial purposes, as had been the case with the sale of indulgences. Consequently, the Reformers laid stress on the idea that the people no longer had to go through an intermediary, such as a priest in order to receive and understand God’s Word. They need not do so since they were already priests themselves (Revelation 1:6).

This notion, often called “the priesthood of all believers” also meant that the Scripture had to be both accessible and understandable to the clergy and laity alike. This new theological emphasis explains why prominent Reformers, like Tyndale and Luther, set out to translate the Scriptures into languages beyond simply Latin (as Jerome had accomplished in the 4th Century with his Latin Vulgate) and into the languages of the common man of their own day.

The privilege inherent in “the priesthood of all believers” theological construct also meant that literacy was necessary so that the common man could both read and understand the Bible. Thus, the Reformation introduced great advances in public education for the purpose of erasing illiteracy.

The Reformers’ Selective Literalness

Although the Reformers were literal in their approach to Protology (the doctrine of Beginnings), Christology (the doctrine of Christ), Soteriology (the doctrine of Salvation), and Bibliology (the doctrine of the Scripture), other doctrines, such as Ecclesiology (the doctrine of the Church) and Eschatology (the doctrine of the End) were treated in an entirely different matter. Despite their emphasis upon literally interpreting some aspects of Scripture, Luther and Calvin did not go far enough in applying a literal interpretation to all areas of divine truth.

In fact, Calvin seems to have ignored much of God’s prophetic Word. Despite having written commentaries on almost every book of the New Testament, Calvin failed to write a commentary on the Book of Revelation. When Calvin did pay attention to prophetic texts, he seemed preoccupied with employing the Alexandrian and Augustinian method of interpretation, and he held in contempt those who rejected his allegorical approach.

The Reformers’ retention of the allegorical method of interpretation in the area of biblical Eschatology is also evident in the way they took the prophecies aimed at a future Babylon and the Antichrist and redirected them so as to make it seem as if these prophecies were instead speaking of the Roman Catholic Church. Such an interpretation was advanced at the expense of the literal sense of these passages.

Because the Reformers spiritualized prophecy, they rejected Premillennialism as being “Jewish opinions.” They maintained the Amillennial view which the Roman Catholic Church had adopted from Augustine.

The Reformers Selective Reforms

Despite the Reformers’ doctrinal progress in select areas, it is simply a matter of historical naïveté to assume that they made a clean break with Roman Catholicism back in the 16th Century. On the contrary, as Roman Catholics themselves who had even initially sought to remain within the Catholic Church, they dragged many vestiges of Roman Catholicism with them into their infant and newly developing Reformed Theology.

In addition to the retention of Augustinian Amillennialism, there were other Roman Catholic holdovers as well. One was the practice of infant baptism. Luther considered infant baptism a sacrament and therefore a means of grace. Still another holdover related to the doctrine of Consubstantiation, which appears to be only a slight modification of the doctrine of Transubstantiation.

Yet another carryover related to the Roman Catholic Church’s view that it was the sole representative of the kingdom of God upon the earth. This Romanist failure to distinguish between the Church and God’s earthly kingdom program for Israel carried over into Calvin’s Geneva. There, Calvin sought to reconstruct a society through the imposition of the Mosaic Law. This social experiment resulted in dire societal consequences.

Finally, it must be pointed out that some of the vitriolic anti–Semitism of the Middle Ages also found its way into the Reformation movement. After all, it was the respected and revered church reformer Martin Luther who, late in his life and frustrated at the Jews’ unwillingness to receive Christ on the basis of faith alone, wrote a scathing tract against the Jewish people entitled, On the Jews and Their Lies. This tract contains numerous anti–Semitic rants.

Although some claim that Luther’s level of anti–Semitic vitriol is not found in the work of John Calvin, such a claim is without merit. For example, note how Calvin’s correction of distinguished Jewish scholar Rabbi Barbinel in Calvin’s commentary on Daniel 2:44 laid bare the true intentions of the Reformer’s heart toward the Jewish people: “But here he [the rabbi] not only betrays his ignorance, but his utter stupidity, since God so blinded the whole people that they were like restive dogs…I have never found common sense in any Jew.”

Reasons for the Reformers’ Inconsistency

With these aforementioned Catholic hangovers remaining, we might ask why did the Protestant Reformers not also reform the Church in these other areas as well?

Several possibilities can be given. Perhaps they were fatigued. They had already sacrificed greatly, and in some cases ultimately, in order to achieve what they did. To require them to take on any more beyond their monumental achievements would have been unrealistic, to say the least.

Also, these other doctrinal areas involving such things as Bible prophecy were not their focus. Their primary battle with the Roman Catholic hierarchy was over the issue of salvation. Any other theological subject matter was simply outside their narrow purview.

Consistent Literal Interpretation

Dispensationalists should be credited for completing the interpretive revolution begun by the Protestant Reformers. The Reformers deserve credit through the employment of the right methodology, a literal interpretation, to some of the Bible. Yet, as has been demonstrated, Reformed Theology continued to allow much allegorization of the Scripture, especially as it related to Ecclesiology and Eschatology.

Dispensationalism, on the other hand, as it came into its own roughly two centuries after the Reformation, took the Reformation method of interpretation and applied this same method to the totality of Scripture.

When such a consistent application of literalism is followed (taking into account figures of speech when they are textually conspicuous), what rapidly re–merges is Premillennialism, or the very Chiliasm initially espoused by the Antioch school of interpretation that dominated the life of the Church for its first two centuries.

Just as the Reformers demonstrated that literalism was the essential prerequisite necessary to restore the five “solas” to Christendom, Dispensationalists demonstrated that literalism was also an essential prerequisite necessary to restore to Christendom both Premillennialism and pre–Tribulationalism (the belief that the rapture will occur before the future Tribulation).

What makes Dispensationalism unique as a theological system is not merely its emphasis upon a literal, grammatical, historical method of interpretation. Many theological systems, such as Reformed Theology, selectively incorporate this method. Rather, Dispensationalism remains unique in its insistence in consistently applying the literal method of interpretation to the totality of biblical revelation. This approach causes the interpreter to recognize that Israel and the Church are unique.

Literalism’s Restoration of Important Doctrines

When it is understood that God has separate programs for Israel and the Church, such theology acts as a natural deterrent against the Church from claiming Israel’s earthly promises through the allegorical method of interpretation. Such a belief prevents the Church from seeing itself as the reigning New Israel. And it keeps the Church from misapplying Israel’s Law of Moses to itself, as was done in Calvin’s Geneva.

The Israel–Church distinction also helps the Church to see that God is not finished with Israel but rather has a special end time plan for her that will play out nationally. Comprehending this future for Israel acts as a restraint necessary to curb Anti–Semitic impulses among the Gentile–dominated Church in the present. The Israel–Church distinction also assists the Church in understanding that she will not be in Israel’s Tribulation period. Thus, the Israel–Church distinction furnishes the proper foundation for embracing a Pre–Tribulation rapture.

Although none of these concepts were retrieved by the Protestant Reformers and although none are found in today’s Reformed Theology, we still owe the Reformers a debt of gratitude since they introduced the correct literal interpretive methodology.

Giving Thanks

As we celebrate the five–hundred–year anniversary of Martin Luther nailing the ninety–five theses to the cathedral door in Wittenberg, Germany, let us rejoice in the fact that this event was used by God to trigger what is now known as the Protestant Reformation. However, at the same time, let us not idolize the Reformers based upon the faulty assumption that the Reformation instantaneously cured all the ecclesiastical ills introduced by the Alexandrian, Augustinian allegorical method of interpretation of the 4th Century.

The Reformation did introduce doctrinal progress. But perhaps more importantly, it also furnished the seed of literal interpretation that would be used by subsequent generations to restore doctrinal wholeness and health to Christ’s Church.