From Communism to Christianity

A Remarkable Story of Change

Some stories are so amazing that they are truly stranger than fiction. The story I want to share with you is true, but it would be beyond the imagination of a novelist or screen writer. It is the story of the life of Helen Joy Davidman.

Joy, as she was always called, was born in the Bronx in 1915 to second generation Jewish immigrants from Poland and Russia.

Her parents were both educators in the New York City public school system. Her father was a principal, and her mother was an elementary school teacher.

A Bright but Rebellious Girl

They naturally took a special interest in Joy’s education from the moment she was born, and they very quickly discovered that she was a child prodigy with a photographic memory. She was a voracious reader and had read H. G. Wells’ Outline of History by the time she was 9 years old. At age 12 she announced to her parents that she was an Atheist. That didn’t upset them because they had both become secular Jews who were more interested in being Americanized than in maintaining the religion of their forefathers.

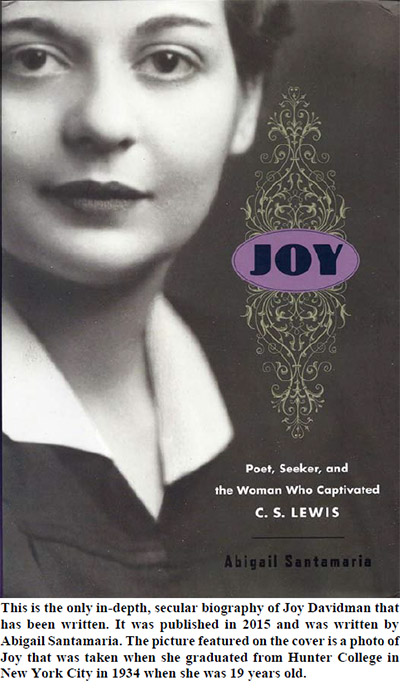

Joy started writing poetry and short stories at an early age and was becoming an accomplished writer by the time she entered Hunter College at the age of 15. Within a year she had her first sexual liaison with a professor who was old enough to be her father. Shortly after that encounter, she announced that she no longer believed in standards of right and wrong. She referred to moral codes as “ugly things” and declared, “I’ve converted to Hedonism.”1

At age 19 Joy was accepted as a graduate student at Columbia University where she began working on a Master’s degree in English Literature, with a minor in French. She completed that degree in a year’s time.

Spectacular Literary Success

Upon graduation, Joy began teaching high school — a job she hated. She poured herself into writing and had several of her poems accepted for publication in the prestigious Poetry magazine. During this time, she developed a friendship with the renowned poet, Stephen Vincent Benét.

Benét was so impressed with her poetry that he nominated her to spend the summer of 1938 at the highly regarded Mac– Dowell Colony in New Hampshire. This was a rural haven where artists of all types could work in seclusion, free from routine distractions. She was accepted by the colony, and she spent the summer writing and interacting with 62 other writers, composers, painters and sculptors.

When Joy was at the colony she received word from Yale University that she had won the Yale Younger Poet’s Award for 1938. The judge had been her mentor, Stephen Vincent Benét. This award brought her national attention and confirmed her intention to become a professional writer.

But an even greater accolade was to come. In January of 1939, at age 24, she was given the poetry prize by the National Institute of Arts and Letters. The first recipient of this prize had been Robert Frost in 1931.

A Difficult Person

Joy had always been a socially awkward person. Combine that with her rebellious spirit and condescending intellect and you end up with a personality that was intolerable to most people. The awards made the situation even worse as her ego got out of hand.

Words people used to describe her included aggressive, impertinent, intolerant, opinionated, rebellious, pompous, impudent, uninhibited, abrasive, hot–tempered and brash. Joy was fully aware of how she was perceived, but she could care less.

Additionally, Joy was a person who cared very little about her external appearance. She was usually described as frumpy or matronly.

Her Commitment to Communism

Joy’s demeanor fit well with her new–found passion for Communism and its rejection of normative values. She had become a member of the party early in 1938. She always claimed that her decision to become a Communist was spurred by her compassion for the suffering masses of the Great Depression.

As is the case with most converts to anything, Joy threw herself passionately into her newly discovered secular religion. Consequently, before long, she was added to the staff of a Marxist weekly literature magazine called New Masses.

Her Marriage

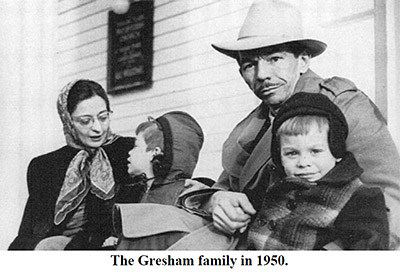

Through her activities in the Communist Party, Joy met a writer named William (Bill) Lindsay Gresham. They started dating and ended up getting married in August of 1942 when Joy was 27 years old.

The marriage was in trouble from the start. Bill proved to be an abusive alcoholic and a serial adulterer. He never tried to cover up his extra–marital affairs, nor did he try to defend them. He simply could not see anything wrong with them.

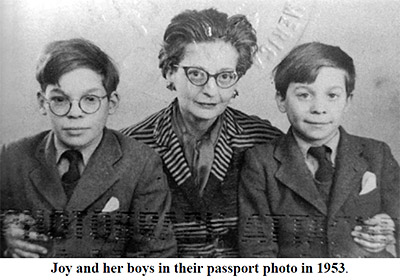

The couple gave birth to two boys — David in 1944 and Douglas in 1945. The stress of dealing with an alcoholic, unfaithful husband and two small boys caused Joy to start drifting away from her heavy involvement in the Communist Party.

An Unexpected Conversion

The turning point for Joy came in 1946 at age 31 when she came to the end of herself. She felt completely defeated and emotionally depleted. In the midst of this personal crisis, she had a spiritual experience which she described as follows:2

…for the first time my pride was forced to admit that I was not, after all, “the master of my fate” and “the captain of my soul.” All the defenses — the walls of arrogance and cocksureness and self–love behind which I had hid from God — went down momentarily — and God came in.

She suddenly found herself on her knees in prayer and confessed, “I must say I was the world’s most surprised atheist.”3 Amazingly, she had almost instantaneously made the transition from Atheism to Theism. But that did not make her a Christian. She still had a long way yet to go.

Discovering C. S. Lewis

She immediately began to search for some way to manifest her newly found belief in God. She went to a Presbyterian church where she was baptized. But it was only a religious rite that she felt she ought to do as a manifestation of her rejection of Atheism.

Proof of this is the fact that she soon stumbled across L. Ron Hubbard’s book, Dianetics, which was published in 1950. The book claimed to be a manual for mental health, but Hubbard very quickly developed his teachings into a religious cult called Scientology. Both Joy and her husband became practitioners and teachers of Dianetics.

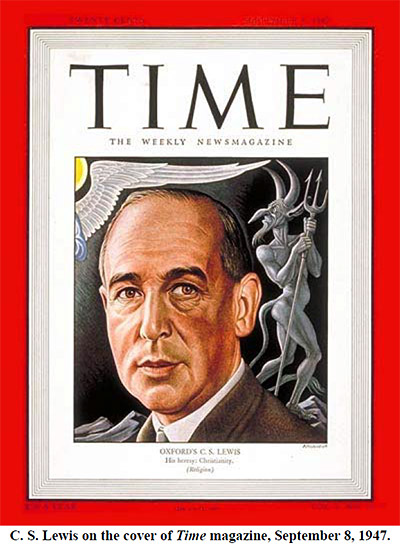

But Joy kept searching, and when she realized that Hubbard was converting his fans into a cultic group, she started pulling away from Scientology and began reading Christian writings. That’s when she encountered C. S. Lewis, who had been featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1947 as one of Christendom’s foremost defenders of the faith. Lewis at that time was a renowned professor of Medieval Literature at Oxford University in England.

In January of 1950, when Joy was 35 years old, she wrote her first letter to Lewis. It was full of theological questions. Lewis had never head of her, but he was deeply impressed by her intellect and erudition — also her humor. He responded in depth to her questions, and they soon became “pen–friends.”

A Family Crisis

In 1952, Joy’s cousin, Renée Pierce (the daughter of her father’s sister) came to live with Joy and her family. Renée’s husband was also an abusive alcoholic, and she fled from him, seeking protection for herself and her two children with the Gresham family.

Meanwhile, Bill’s lifestyle was so out of control that Joy felt the need to separate from him for a while and seek counsel. She decided to go to England to meet her “pen–friend” and seek his insights. She arranged for Renée to keep her children and look after Bill, and she departed for England in August 1952. She had arranged to stay with another of her pen–pals — a lady in London.

Meeting Lewis

Upon arrival, she contacted Lewis and invited him to have lunch with her and her friend. Lewis accepted the invitation and brought his brother Warren, with him. Both Lewis and his brother (who lived together) found Joy to be “enthralling,” and Warren noted in his diary that she kept Jack (as Lewis’ family and friends always called him) “laughing uproariously.”4 Additional luncheon meetings finally led to an invitation for Joy to spend a fortnight (two weeks) with Lewis and his brother before her return to the States. This period of time included Christmas of 1952.

During her time at the Lewis household, Joy read the manuscript of a book on prayer that Jack was writing, and she made suggestions for improving it. In return, Jack gave her suggestions for editing the book she was working on called Smoke on the Mountain, which was her commentary on the Ten Commandments.

Another Family Crisis

Before Joy departed for the States, she received a letter from her husband in which he informed her that he had fallen in love with her cousin, Renée, and they had decided to get married. He asked Joy for a divorce. Joy shared the letter with Jack and asked for his advice. He strongly advised her to divorce Bill because of his infidelity.

When Joy returned home in January of 1953, Bill was drunk. He beat her up and choked her. That was the last straw for her. She decided to return to England with her sons. Bill proceeded to divorce her and marry Renée.

Her Return to England

Joy arrived back in England in November 1953. She rented an apartment, put her boys in boarding school, and set about to revive her relationship with the Lewis brothers. Jack and Warren continued to be enthralled with her. But Jack’s professor friends were not the least bit impressed. They considered her to be a typical “ugly American” — pushy, abrasive, over–bearing and vulgar.

She and Jack began to see each other regularly. They would take long walks together, debate theology and discuss English literature.

Jack was 55 years old at the time, 17 years older than Joy. He had been a lifelong bachelor. His mother had died of cancer when he was only ten years old. His only female companionship had been a woman named Mrs. Jane Moore, the mother of his deceased war buddy, Paddie Moore. Lewis had made a pact with Paddie that if either of them were killed in the war, the survivor would take care of the other’s family. True to his word, Jack ended up caring for Mrs. Moore for the rest of her life. She died in 1951. She was 27 years older than Jack, and he always referred to her as “mother.”

Joy filled a void in Jack’s life. Despite all her overwhelming faults, he deeply enjoyed her profound intellect and he fell in love with her mind. Gradually, he began to fall in love with her emotionally. Nor was she the only one he cherished. That’s because Jack had become very attached to her two sons who were 12 and 13.

A Legal Crisis

In 1956 another crisis arose in Joy’s life when the British Foreign Office informed her that they were not going to renew her permit to remain in England. Jack could not face the possibility of losing the trio he had grown to love so much. His response was to propose a civil marriage which would enable Joy and her boys to remain in England. The marriage took place on April 23, 1956. The act was, in effect, a naturalization process for Joy.

Jack and Joy had decided that for the time being their marriage would remain a secret. Joy continued to live at her house and Jack at his. But they visited each other frequently, and before long, rumors began to circulate. Jack decided that to avoid malicious gossip, he would seek to have their marriage blessed by the Church. But the Bishop of Oxford refused because Joy had been divorced.

A Health Crisis

Meanwhile, in June of 1956 Joy began experiencing pain in her left hip. In October, the hip suddenly gave way and she took a bad fall which produced excruciating pain. She was rushed to a hospital where it was discovered that she had cancer in her left femur and a malignant tumor in one of her breasts.

In December, as her condition grew steadily worse, Jack decided to announce their marriage in the newspaper.

By late January of 1957 it was clear that her radiation treatments were having no effect. Her pain was constant, and there were signs of imminent death. Jack asked an Anglican priest friend of his to pray for Joy’s healing. He agreed.

When the priest arrived at the hospital and saw Joy’s pitiful condition and learned of her desperate desire for a church wed–ding, he agreed to conduct the ceremony then and there. And so, Jack and Joy’s marriage was consecrated by the Church on March 21, 1957. He was 59 and she was 42.

Joy was now ready to die. The doctors gave her two months to live, at most. But, instead, she suddenly began to improve. Throughout the summer and fall, she continued to gain strength, and in January 1958 her cancer was proclaimed to be “arrested.” The doctors were amazed.

Days of Happiness

She moved into Jack’s house and immediately set about to remodel it inside and out — something it badly needed. As they settled into life as husband and wife, Jack began experiencing the happiest days of his life.

In the Summer of 1959 they began traveling throughout England and Ireland, but in October, exactly two years after her diagnosis, the cancer returned with a vengeance. They sensed there was little time left, so they decided to take one last trip to the place Joy had always dreamed of visiting — Greece. They went in April of 1960, and by the time they got back home, Joy was very weak. Tests revealed that the cancer had spread throughout her body.

Death

In July of 1960, at age 45, Joy had to be hospitalized again. And on the evening of July 13, with Jack at her side, she smiled and said, “I am at peace with God.”5 Those were her last words.

Jack later summarized his wife and their relationship with these remarkable words:6

Joy was a splendid thing; a soul straight, bright, and tempered like a sword. But not a perfected saint. A sinful woman married to a sinful man; two of God’s patients, not yet cured.

Jack’s words for her tombstone were put in poetic form:7

Here the whole world (stars, water, air And field, and forest, as they were Reflected in a single mind), Like cast off clothes, was left behind In ashes, yet with hope that she, Reborn from holy poverty, In lenten lands, hereafter may Resume them on her Easter Day.

Jack died three years later on November 22, 1963. His death went almost unnoticed because that was the day that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

And so you have it — the incredible story of how an American Jewish Communist became the wife of a British professor who was Christendom’s greatest defender of the faith.

Some Summary Thoughts

The life of Joy Davidman is just another example of how God can transform anyone through the power of His Holy Spirit — and how He desires to do so. The Bible says that God does not wish that any should perish, but that all should come to repentance (2 Peter 3:9). No matter how repulsive a person may be in his or her beliefs, personality or lifestyle, God desires for that person to come to know Jesus as Lord and Savior.

There are three other points I would like to make, and then I will draw this story to a close.

First, in 1948, Jack began writing his spiritual autobiography which he titled, Surprised by Joy. That was two years before he received his first letter from Joy Davidman. The title of this remarkable book, which was finally published in 1955, turned out to have a double meaning.

Yes, Jack was overwhelmed with spiritual joy when he came to know Jesus as his Lord and Savior at the age of 33. But, later, he was also impacted with mental and physical joy when Joy Davidman came into his life.

My second point relates to the remarkable parallels in the lives of Joy and Jack. Just as Joy announced at age 12 that she was an Atheist, Jack did the same thing at age 15. At age 31, Joy had a deeply spiritual experience that transformed her from an Atheist to a Theist. The same thing happened to Jack at the same age. And his description of the event sounded just like Joy’s: “I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England.”8 Joy did not become a Christian until two years after her conversion to Theism and the same was true of Jack.

Spiritually they followed exactly the same path. But their personalities were as different as night and day.

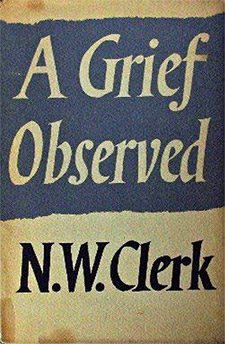

My third observation relates to the powerful book that C. S. Lewis wrote in response to Joy’s death. It was titled A Grief Observed. The book is a daily journal of Jack’s thoughts as he grieved over the loss of his wife.

A Chronicle of Grief

All of Jack’s previous books related to religion had been intellectual exercises in which he applied his profound logic to theological problems. But this book was produced out of raw emotion, speaking from a broken heart.

It was published in 1961 under the pseudonym, N. W. Clerk. Its true author was not revealed until 1963 after Jack’s death. It is believed that Lewis felt like the book would be too great a shock to his admirers — the reason being that the book lays bare his anger with God over Joy’s death.

For example, the book begins with Lewis asking, “Where is God?”9 He then asks another profound question: “Why is He so present a commander in our time of prosperity and so very absent a help in time of trouble?”10

Keep in mind that this is the foremost defender of the Christian faith who is asking these questions.

Lewis follows up these questions by quickly stating that he is not in much danger of ceasing to believe in God. “The real danger,” he explains, “is of coming to believe such dreadful things about Him.”11 For example, is He truly a God of love, grace and mercy, or is He a “Cosmic Sadist”?12 Lewis concludes this section by saying he feels like God has slammed a door in his face.

But as Jack begins to emerge from his grief, he looks back over his struggle with God and says that he can see that God was with him all along, but that God was unable to comfort him because he was like a drowning man flailing around and pushing away anyone wanting to help.13

At one point in the book, Jack observes that throughout his ordeal, people have been telling him, “God is testing your faith.” But he concludes that they have been wrong. He writes:14

God has not been trying an experiment on my faith or love in order to find out their quality. He knew it already. It was I who didn’t …He always knew that my temple was a house of cards. His only way of making me realize that fact was to knock it down.

This book has often been characterized as a “crisis of faith.” I can understand how it could be viewed that way. But in actuality, it was a demonstration of Lewis’ deep faith. For throughout the book he is talking with God, not denying Him.

Like King David in his psalms, Jack was just being truthful with God. His heart was hurting, and he said so, not mincing any words. And that is what I love about David’s psalms. When he hurts, he says so. When he’s angry or doubtful, he says so. When he encounters joy, he cries out to God in thankfulness. He had an honest and open relationship with God.

So did C. S. Lewis. Do you?

References:

1) Abigail Santamaria, Joy: Poet, Seeker, and the Woman Who Captivated C. S. Lewis (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015), page 33.

2) Lyle W. Dorsett, And God Came In: The Extraordinary Story of Joy Davidman (Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, first edition in 1983, second edition in 2011), page 60. This is an excellent spiritual biography.

3) Ibid.

4) Santamaria, page 229.

5) Dorsett, page 156.

6) C. S. Lewis, A Grief Observed, originally published under the name of N. W. Clerk in 1961 in England by Faber & Faber, Limited. The quotation is found on page 35 of the fourth American edition by The Seabury Press in New York.

7) Dorsett, page 158. A photo of the tombstone appears on page 107.

8) C. S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life (London: Harvest Books, 1955), pages 228-229).

9) Lewis, A Grief Observed, page 9.

10) Ibid.

11) Ibid., pages 9-10.

12) Ibid., page 27.

13) Ibid., page 38.

14) Ibid., page 42.