Israel’s 60th Anniversary

Understanding God’s prophetic timeclock.

During this year (2008) the 60th anniversary of the independence of Israel will be celebrated on May 8th (the 5th of Iyar on the Jewish calendar).

In 1948 the 5th of Iyar fell on May 14th, and that was the momentous day when David Ben Gurion read the Israeli Declaration of Independence at a small museum in Tel Aviv before an audience of about 200 people. Only one photographer was present.

The first nation to recognize the new state was the United States. President Harry S. Truman issued the recognition statement only 11 minutes after the declaration went into effect. American recognition proved to be one of the crucial keys to the survival of Israel.

What prompted President Truman to act so quickly and so decisively? It’s only in recent years that the full story has emerged.

Relevant Bible Prophecies

But first, some background. The Hebrew prophets were given many prophecies concerning the Jewish people. It was prophesied that their disobedience would lead to their worldwide dispersion from their homeland of Israel and that they would be persecuted wherever they went (Deuteronomy 28:58-67). But the Lord promised that a remnant would be preserved (Jeremiah 30:11) and that one day they would be regathered in unbelief to their homeland (Isaiah 11:10-12) where their state would be reestablished (Isaiah 66:7-8).

In 70 AD when the Romans put down the First Jewish Revolt, the dispersion of the Jews began. After the Second Revolt (132 – 135 AD), the Romans accelerated their dispersion of the Jews. By that time they were so disgusted with the stubbornness of the Jews that they decided to further humiliate them by changing the name of their homeland from Israel to Palestine — a Latin term for Philistia. In other words, they renamed the land in honor of the age-old enemies of the Jews — the Philistines.

Everywhere the Jews roamed for the next 1,800 years, they were persecuted, just as had been prophesied. But, amazingly, they kept their identity, unlike any other nation that had become so scattered.

God Begins to Move

In the late 19th Century God raised up a visionary by the name of Theodore Herzl. He was a Hungarian Jew who lived in Vienna. In 1896 he published a booklet in which he called for the Jewish people to return to their homeland. The booklet sparked the imagination of the Jewish people worldwide and led to the First Zionist Congress which was held in Basel, Switzerland in 1897. After this historic assembly had adjourned, Herzl wrote in his diary these prophetic words:1

“At Basel I founded the Jewish State. If I said this out loud today, I would be greeted by universal laughter. In five years perhaps, and certainly in fifty years, everyone will perceive it.”

The next great milestone came in 1917 as a result of World War I. During that war the Turks sided with the Germans. Their realm, called the Ottoman Empire, included most of the lands of the Middle East, including Palestine which they had ruled for 400 years. When the Germans lost the war, the Turks went down with them, and their empire was divided up among the Allied victors. In a secret pact signed in 1916 (called the Sykes-Picot Agreement), the British and French agreed to divide the Middle East between themselves when the war ended. Britain received Palestine while the French were given Syria, Lebanon, and a part of Iraq.

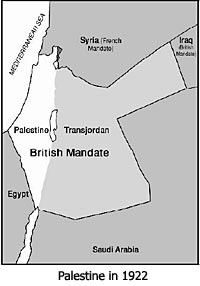

In November of 1917 the British issued the Balfour Declaration in which they announced their intention to create a homeland for the Jewish people within the territory of Palestine. At that time, Palestine consisted of all of modern day Israel and Jordan — an area of 45,000 square miles (see the map below).

But hardly had the ink dried on the Balfour Declaration before the British decided in 1922 to give two-thirds of Palestine to the Arabs in order to secure their access to Arab oil. This led to the creation of a Palestinian state called Transjordan (see the map below).

This British action to placate the Arabs left a small area of land for the promised Jewish state — a sliver of land only 10,000 square miles in size, smaller than Lake Michigan or the state of New Jersey.

The League of Nations Mandate

Immediately thereafter, the League of Nations entrusted what was left of Palestine to Britain as a Mandate, and the British began to rule the land with the ultimate goal of guiding it to self-government. But the British soon found themselves in the middle of a bloody Jewish-Arab struggle for the land.

As the struggle intensified and more and more British soldiers were killed, the British people began to pressure the government to look for a way to extricate themselves from the bloodbath. The pressure mounted in late 1946 when Winston Churchill, leader of the opposition to the Labor Government, began publicly urging an end to the Mandate. He declared, “If we cannot fulfill our promises to the Zionists, we should, without delay, place our Mandate for Palestine at the feet of the United Nations, and give them due notice of our impending evacuation from the country.”2

At about the same time, in October 1946, President Truman endorsed the establishment of a “viable Jewish state” in Palestine.3 Most people assumed that the timing of this announcement was probably prompted by the mid-term elections for Congress that were coming up in November.

Clement Attlee (British Prime Minister from 1945 to 1951) reluctantly gave ground to the mounting pressure. On February 18, 1947, Attlee’s spokesman announced: “His Majesty’s Government have of themselves no power under the terms of the Mandate to award the country to the Arabs or the Jews, or even to partition it between them… We have, therefore, reached the conclusion that the only course open to us is to submit the problem to the judgment of the United Nations.”4

This action by the British government was most likely a ruse to satisfy public opinion, for no one in the government believed that there were enough votes in the United Nations to end the Mandate. The Russians and their allies were staunchly pro-Arab, and their bloc, together with the Arab states, represented enough votes to prevent a British withdrawal that might lead to a partition of the land which the Arabs wanted all to themselves.

The British announcement led to the calling of a special session of the General Assembly of the United Nations to deal with what was dubbed as “The Palestine Question.” The session was held at Flushing Meadows, New York, from April 28th to May 15th of 1947.

Two significant developments came out of this special session. First, the General Assembly decided to set up an eleven member investigating committee called The United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP). Its purpose was to study the problem of Palestine and propose a solution.5

The second development was a diplomatic bombshell in the form of a surprise announcement by the Soviet Ambassador, Andrei Gromyko. He attacked what he called the “bankruptcy of the mandatory system of Palestine” and then went on to endorse “the aspirations of the Jews to establish their own state.”6

Why the Russians did this about-face is still a mystery to this day. Most likely, they were motivated by a desire to force the British to withdraw from the Middle East, believing that the much more numerous Arabs could fill the resulting political vacuum, ending up with a weak Arab state that would be dependent on the Soviets. Whatever the reason, the Russian move caught the British flat-footed. They were suddenly faced with the reality that the process had gone too far for them to put the brakes on it.

The United Nations Solution

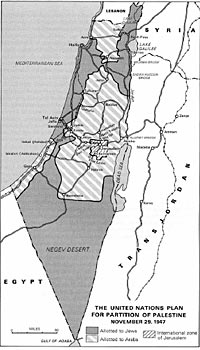

In late August the UNSCOP report was released. The Committee agreed unanimously to recommend ending the mandate as soon as possible. The majority (7 to 3, with one abstention) recommended partition of Palestine into Arab and Jewish states. The minority called for a federation with Arab and Jewish cantons.7 The Jews reluctantly accepted the report. The Arabs passionately rejected it and threatened war should the United Nations approve partition.

The UNSCOP proposal produced an Arab state composed of three areas: the Gaza Strip, the Central Highlands of Judea and Samaria, and the Western Galilee (see the map below). These areas were intertwined serpent-like with the areas allotted to Israel: the Eastern Galilee, the Coastal Plain, and the Negev Desert. The Arab state would embrace 4,500 square miles, with 840,000 Arabs and 10,000 Jews. The Jewish state would encompass 5,500 square miles, with 538,000 Jews and 397,000 Arabs. Jerusalem and Bethlehem were to be internationalized. These cities contained a combined total of 100,000 Jews and the same number of Arabs.8

On November 29, 1947,the United Nations voted to adopt the UNSCOP recommendations to partition Palestine and create both Jewish and Arab states. The vote in favor totaled 33 and included the United States and Russia. Thirteen voted against, including all eleven Muslim states. There were ten abstentions, including Britain. The resolution required a two-thirds vote of those voting, so it passed with votes to spare. The deciding bloc turned out to be the nations of Latin America. All of them, with the exception of Cuba, voted in favor of the resolution.9

Jews all over the world broke out in rejoicing, but the Jewish leaders knew that the fight was not over. As the Arabs rattled their sabers, the Jews launched a massive public relations campaign aimed at keeping the United States committed to partition.

The Response to the United Nations Vote

In December of 1947 the White House received more than 100,000 letters and telegrams concerning Palestine.10 In the midst of the escalating and conflicting pressure, President Truman wrote to one of his assistants: “I surely wish God Almighty would give the Children of Israel an Isaiah, the Christians a St. Paul, and the Sons of Ishmael a peep at the Golden Rule.”11

On December 3rd the British announced they would terminate their League of Nations Mandate for Palestine on May 15, 1948. That same day the Arabs announced they would “defend their rights.”12

The British announcement and the hostile Arab response to it prompted a reconsideration of the American position in support of partition. The speed at which the process was moving seemed to spook the State and Defense Departments.

James Forrestal, the Secretary of Defense, together with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, reminded President Truman of the critical need for Saudi Arabian oil. The President responded by saying he would “handle the situation in light of justice, not oil.”13 Forrestal also told the President that in his opinion, “the Arabs would push the Jews into the sea.”14

The pressure from the State Department was even more intense because its career bureaucrats were all pro-Arab. They began to develop an alternative to the partition plan. Their idea was to replace the League of Nations Mandate with a United Nations Trusteeship.15 As the new year of 1948 arrived, extreme tension mounted between the White House and what President Truman called “the striped pants boys” at the State Department.16

The President’s contempt for the State Department did not apply to his Secretary of State, General George C. Marshall, even though Marshall was the strongest opponent to the establishment of the Jewish state. Truman greatly admired Marshall, and Marshall had the highest degree of public respect of anyone in the Truman Administration. The Secretary’s “Marshall Plan” for the reconstruction of Europe had caught the public imagination and had been hailed as a lifesaver throughout Europe. Marshall’s outstanding leadership resulted in his being selected as Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” for 1947. Regarding Palestine, Marshall favored a “unitary state under a United Nations Trusteeship.”17

There were only two people in the Truman Administration who strongly supported the partition plan, and both of them were presidential advisers — David Niles and Clark Clifford. Clifford was Truman’s White House Counsel and confidant. Niles, who was Jewish, was one of only two Roosevelt aides who were retained by Truman when he became President. Niles was the President’s counselor regarding minority issues and patronage.

As a Jew, Niles had a natural sympathy for the terrible plight of the Jewish people who had survived the Holocaust. Clifford, on the other hand, based his support of Israel on his reading of ancient history and the Bible. He firmly believed the Jewish people were entitled to their homeland.18 Niles kept the key Zionist leaders informed of what was going on in Washington and within the White House. Clifford served to encourage the President to hold firm to his commitment to a Jewish state.

When the Zionist leaders learned of the strong opposition within the Truman Administration to the establishment of a Jewish state, they decided to send their foremost statesman and spokesman to Washington, D.C., to confer with the President. He was Chaim Weizmann (1874 – 1952).19

Two Crucial Jewish Voices

Dr. Weizmann was a Russian Jew who had migrated to England where he had become a professor of chemistry. During World War I he greatly aided the British when he developed a synthetic form of acetone which was essential in the manufacture of cordite explosive. Some historians have suggested that this contribution to the British war effort is what prompted the Balfour Declaration. Weizmann served twice as president of the World Zionist Organization (1920-1931 and 1935-1946).

Despite his immense prestige, when Weizmann arrived in Washington, D.C., in March 1948, President Truman refused to see him. This was because the President had become irritated over all the Jewish pressure that was being applied to the White House, particularly by some American rabbis who had been very tactless. Also, the President had already met with Dr. Weizmann the previous November, and during that meeting, the President had assured him of his support for a Jewish state.20

It was at this critical point in time that President Truman’s dear friend and former business partner, Eddie Jacobson, decided to intervene. The two had been partners in the clothing store business in Kansas City from 1919 to 1922. In his memoirs, Truman wrote that he ever had a “truer friend.”21

Jacobson was Jewish. He was not a Zionist, but he had a great compassion for the sufferings of the Jewish people. When he learned that Truman was refusing to see Weizmann, he traveled to Washington, D.C., to urge his old business partner to change his mind. Truman was impressed: “In all my years in Washington,” he wrote, “he had never asked me for anything for himself.”22

In response to Jacobson’s fervent personal plea, President Truman agreed to see Dr. Weizmann off-therecord on March 18th. They talked for almost an hour, and once again, the President assured Weizmann of his support for a Jewish state.23

A Diplomatic Earthquake

The very next day the State Department blind-sided the President when Warren Austin, the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, announced that the United States had decided to recommend abandoning the partition plan in favor of a UN Trusteeship!24 Truman wrote with a fury in his diary:25

“This morning I find that the State Department has reversed my Palestine policy. The first I know about it is what I see in the papers. Isn’t that hell? I’m now in the position of a liar and a doublecrosser. I never felt so in my life.”

Truman was particularly infuriated because he had specifically insisted that he be shown Austin’s speech in advance. The State Department had ignored this command.26 What made the situation even more painful was that the President could not publicly repudiate Austin. To do so would make it appear that he was not in control of his own foreign policy. Reflecting upon this event in his memoirs, Truman wrote:27

“The difficulty with many career officials in the government is that they regard themselves as the men who really make policy and run the government. They look upon elected officials as just temporary occupants. Every President in our history has been faced with this problem: how to prevent career men from circumventing presidential policy.”

Eddie Jacobson returned to the White House on April 11th to urge the President to reverse the State Department announcement. The President assured him “very strongly” that he supported partition and was determined to recognize the new Jewish state.28

The Final Show-Down

But the opponents of partition within the Administration were determined to change the President’s mind. Their all-out effort occurred on May 12th when Secretary of State Marshall and several of his aides went to the White House to meet with the President. To their surprise, President Truman had several of his aides present, including David Niles and Clark Clifford.

The meeting began with a presentation by one of Secretary Marshall’s aides, Robert Lovett. He presented the State Department’s case for a United Nations Trusteeship.

The President then called on Clark Clifford to read a paper he had prepared. In that paper Clifford argued that the recognition of the state of Israel would be “an act of humanity” in response to the Holocaust. He quoted the promise of the Balfour Declaration and he cited verses from Deuteronomy to verify the Jewish claim to the land.29

Marshall became incensed. He considered Clifford to be nothing more than a political operative, and he believed his arguments were politically motivated, designed to guarantee the Jewish vote for the President in the upcoming election. Marshall finally became so agitated that he interrupted Clifford and said, “This is just straight politics. I don’t even understand why Clifford is here!” Truman answered softly, “General, he is here because I asked him to be here.”

Clifford continued. When he finished, Lovett spoke again in rebuttal. He argued that recognition of the Jewish state would be disastrous to American prestige at the United Nations because it would appear only as “a transparent bid” for Jewish votes in the upcoming presidential election in November.

At this point, Marshall spoke again. Looking directly at Truman, he said that if the President were to follow Clifford’s advice, he would vote against the President in the election!

It was an incredible rebuke of the President in front of witnesses. The room fell silent. All sat in shock. Clifford later called it an “awful, total silence.” Truman showed no sign of emotion. Finally, he said he thought it would be best for everyone to “sleep on the matter.”30

The Final Decision

Two days later, on Friday, May 14th, the day of the Declaration of Independence, Secretary of State Marshall called the President and told him that while he could not personally support recognition, he would not oppose it publicly.31

The Declaration was scheduled to take effect at 6:00 p.m. Washington time. Eleven minutes after the effective time, one of the President’s aides, Charlie Ross, announced that the United States was granting de facto recognition to the new state of Israel. The United States thus became the very first nation to recognize Israel.

The American delegation to the United Nations was flabbergasted. Marshall dispatched his head of UN affairs, Dean Acheson, by plane to New York to keep the whole delegation from resigning. Many in the State Department urged Marshall to resign, but he refused. He said the President had the constitutional right to make the decision. However, he refused ever again to speak to Clark Clifford.32

The Aftermath

On May 15th the British High Commissioner in Palestine said his farewells and departed Jerusalem. On May 16th the Provisional Government of Israel met and elected Dr. Chaim Weizmann to serve as Israel’s first president.

Meanwhile the fledgling Jewish state had come under immediate attack from five Arab armies who were determined to destroy the nation at its birth. Attacking from three sides, the armies came from Egypt, Transjordan, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.

This invasion fulfilled a symbolic prophecy given by Isaiah in which he said that the future Jewish state would be born “in one day” and that the labor pains would come after the birth (Isaiah 66:7-8). And so they did, and those labor pains have continued to this day as Israel has experienced one war after another for its survival.

After Truman’s re-election in November 1948, the Chief Rabbi of Israel, Isaac Halvei Herzog, paid the President a visit. He told Truman, “I believe God put you in your mother’s womb so you would be the instrument to bring the rebirth of Israel after two thousand years.”33

In May 1951, David Ben Gurion, the Prime Minister of Israel, visited the President at the White House to thank him for his support. His last meeting with the President occurred in 1952 at a hotel in New York. In an interview which he gave years later, he said:34

“I told him [Truman] that as a foreigner I could not judge what would be his place in American history; but his helpfulness to us, his constant sympathy with our aims in Israel, his courageous decision to recognize our new state so quickly, and his steadfast support since then had given him an immortal place in Jewish history. As I said that, tears suddenly sprang to his eyes. And his eyes were still wet when he bade me goodbye… A little later… a correspondent came up to me and asked, ‘Why was President Truman in tears when he left you?'”

Concluding Thoughts

Was Secretary of State Marshall correct in his assessment of President Truman’s motivations? Was the President’s decision concerning Palestine motivated by politics?

On the surface, this would be easy to believe. After all, New York state had more Jews than the state of Israel, and the President was facing what seemed to be impossible odds. His popularity rating was low and his party was split three ways. Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina was pulling out to run as the candidate of the Dixiecrat Party, a move that threatened to take the Southern states away from the President. And FDR’s former Secretary of Agriculture and Vice President, Henry Wallace, was determined to run on the Progressive Party ticket. This move threatened to attract the liberal wing of the Democrats.

But the historical record seems to indicate that Truman’s decision was deeply rooted in his personal values and his Christian faith. All his life he was a voracious reader. He always claimed that he had read the Bible twice before he even started to school! He knew the history of the Jews by heart, and he understood their biblical claim to the land.35

His heart was revealed early on in April of 1943 when he was serving in the Congress as a Senator from Missouri. He flew to Chicago to speak at a huge rally that was held at Chicago Stadium to urge help for the doomed Jews of Europe. There was no political gain to be made from such an appearance, but Truman went anyway, and he spoke with great passion.

He referred to Hitler as a “mad man,” and he boldly implied criticism of President Roosevelt for not doing enough to help the Jews. Referring to FDR’s “Four Freedoms” speech, Truman observed:36

“Merely talking about the Four Freedoms is not enough. This is the time for action. No one can any longer doubt the horrible intentions of the Nazi beasts. We know they plan the systematic slaughter throughout all of Europe, not only of the Jews, but of vast numbers of other innocent peoples.”

Proverbs 21:1 states that the hearts of rulers are like “channels of water in the hand of the Lord.” The passage goes on to state that God can turn their hearts “wherever He wishes.”

The story of Harry Truman’s decision to support the establishment of a Jewish state and grant it immediate recognition is a story about how God prepares a man to make an historic decision that would fulfill Bible prophecy. First, he was grounded in the Scriptures and was well-acquainted with the history of the Jews. Then, a Jewish man he met in the military during World War I became his best friend and business partner. He was deeply impacted by the suffering of the Jewish people during the Holocaust. And when the time came for his momentous decision regarding Palestine, two of his closest advisors were staunch supporters of Israel. The Lord even touched the heart of Israel’s greatest opponent within the Administration — Secretary of State George Marshall — and at the very last moment, he consented to the President’s course of action.

How else can the pivotal role of Eddie Jacobson be explained, except supernaturally? He was a simple store clerk whom God positioned in the center of Truman’s life, ready to take action at just the right moment.

The Bible says that God made a promise to Abraham that He would bless those who bless the Jews and curse those who curse them (Genesis 12:3). God has been faithful to that promise throughout history.

In May of 1948, President Harry S. Truman greatly blessed the Jewish people. In November, God returned the blessing to him as he won re-election in one of the most astounding victories in history.

Notes

- Marvin Lowenthal, editor and translator, The Diaries of Theodor Herzl (London: Smith Peter, 1958) p. 220.

- Connor Cruise O’Brien, The Siege: The Saga of Israel and Zionism (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986), p. 272.

- John Snetsinger, Truman, the Jewish Vote and Israel (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1974), p. 164.

- O’Brien, p. 272.

- Howard M. Sachar, A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1976), p. 284.

- O’Brien, p. 274.

- Sachar, pp. 284-285. See also O’Brien, p. 277.

- Sachar, p. 292.

- Ibid., p. 294.

- David McCullough, Truman (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), p. 598.

- Harry S. Truman, Memoirs by Harry S. Truman: Years of Trial and Hope, Volume 2 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1956), p. 157.

- Truman, p. 159.

- McCullough, p. 597.

- Ibid., p. 602.

- Ibid., p. 601.

- Ibid., p. 611.

- Sachar, p. 290.

- Bernard Weisberger, interview with Clark Clifford, American Heritage magazine, December 28, 1976.

- The Jewish Visual Library, “Chaim Weizmann,”

www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/weizmann.html, accessed January 3, 2008. - Truman. pp. 157-158.

- Ibid., p. 160.

- Ibid.

- McCullough, p. 608.

- Ibid., p. 609.

- Robert H. Ferrell, ed., Off the Record: The Private Papers of Harry S. Truman (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1997), p. 127.

- McCullough, p. 611.

- Truman, p. 165.

- Edward Jacobson, “Two Presidents and a Haberdasher — 1948,” American Jewish Archives, 1968.

- McCullough, pp. 614-615.

- Ibid., p. 616.

- Ibid,. pp. 617-618.

- Ibid., p. 620.

- Alfred Steinberg, The Man from Missouri: The Life and Times of Harry S. Truman (New York: Putnam, 1962) p. 308. See also, Merle Miller, Plain Speaking: An Oral Biography of Harry S. Truman (New York: Putnam, 1974), pp. 235-236.

- Sachar, p. 312.

- Miller, pp. 52, 230-231.

- McCullough, p. 286.