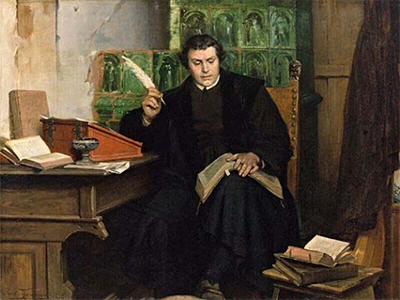

Martin Luther

A Captive to God’s Word

By Dennis Pollock

Dennis Pollock served as an Associate Evangelist for Lamb & Lion Ministries for 11 years before he decided to form his own ministry in 2005 called “Spirit of Grace.” It is a ministry that focuses on conducting evangelistic campaigns in Africa.

Dennis’ wife, Benedicta, is a native of Nigeria, and she is actively involved in the ministry as an event coordinator and teacher.

Dennis is a masterful writer who specializes in writing biographical sketches that illustrate biblical points about the difference in living for Jesus and living for the world. These insightful essays, together with doctrinal teachings are also recorded and released monthly on audio CDs. For information about how to get on Dennis’ mailing list, go to his website at www.spiritofgrace.org.

If one were to read the book of Acts, which describes the phenomenal power and growth of the early Church, without knowing the future history of the Church, he would have to assume that within a few centuries Christianity would surely conquer the whole world. Sadly, the opposite proved true.

Within a few generations the power and the life of the early believers had been reduced to formal ceremony and dead liturgy. Biblical knowledge perished, and ignorance and superstition flourished.

As the centuries rolled by, the Church of Jesus Christ became increasingly impotent, corrupt and irrelevant. Even the knowledge of the most foundational of all Biblical questions — “How do we obtain peace with God?” — was lost.

Luther’s Early Years

(www.biography.com)

Such was the state of the Church when a baby boy named Martin Luther was born on a November day in 1483. Martin’s strict, no–nonsense father soon realized his son was brilliant and began making plans for him to study to become a lawyer. Martin dutifully followed in the path his father had laid out for him, earning a bachelor’s degree in a single year and a master’s degree after that. His sharp mind enabled him to do well in his studies, but he had far more interest in religion and philosophy than he did in law.

Death in the Middle Ages was a reality impossible to ignore. Plagues would sweep through Europe and decimate entire towns. One fourth of children died before the age of five. Disease was rampant.

Luther, always sensitive and often moody, wondered where he stood with God. One day as he was returning to the university after a visit home, a thunderstorm arose. As the lightning and thunder crashed all around him, he feared for his life and called out in desperation to Saint Anna, vowing to become a monk if she would spare his life. When he survived the storm, he was as good as his word and entered a monastery, fully intending to spend the rest of his days there.

A Zealous Monk

Luther went to the monastery not only to fulfill his vow to Saint Anna, but also to save his soul. Like the rest of his generation — including the priests and bishops — he knew nothing of salvation by grace or the nature of the new birth. But to his thinking, the monks, with their austere lifestyles, vows of poverty and chastity, and constant prayers and church services, represented the apex of holiness. If anyone would be allowed to enter heaven, surely the monks would make it.

Luther entered his new vocation with a passion, and determined to be the monk of monks. He practiced self–denial by frequent fasting and sleeping outdoors in the winter without a blanket. He prayed constantly and beat himself with a whip to show God how sincere he was in his desire for holiness and salvation. Luther went to confession as all good monks did, but his confessions were far from ordinary. While the average monk would go over a few basic sins and get it over with, Luther would dredge up everything he could think of from the years past to the present day. He would repeat confessions of sins he had already confessed, thinking perhaps he hadn’t been sincere enough in the previous confession. Sometimes confessing four times a day, his confessions lasted for hours, until his confessors dreaded the approach of their guilt–ridden brother.

Luther later wrote, “I was a good monk, and I kept the rule of my order so strictly that I may say that if ever a monk got to heaven by his monkery it was I.” But his conscience was never satisfied. He began to see God as a cosmic reflection of his earthly father: stern, cold, and utterly impossible to please. He was growing to hate this God whose condemnation he could never escape.

It took a trip to Rome to begin the process of disillusionment. In the Catholic Church, Rome was the holy city, the essence of all that was pristine and godly. When his orders sent him there on a brief assignment, Martin was thrilled beyond words. If ever there should be a suitable place for him to obtain the peace he sought, it would surely be here.

This was the pope when Luther posted his

95 theses.

The End of the Beginning

Upon arrival, he indulged in all the city had to offer, running from one shrine to another, attending masses, and racking up all kinds of spiritual points by visiting the tombs and viewing the bones of dead saints.

But soon his bubble burst as he began to see the prevailing carnality of the priests and church leaders he had assumed would be shining examples of holiness and purity. Sexual immorality was rampant among the priests. Some claimed virtue due to the fact that they only had sex with women. Masses were said hurriedly and without passion or meaning.

When Luther had the chance to say a mass, he was told by the impatient priests to hurry up — “Just get on with it!” Nobody seemed to take God seriously. A terrible, disconcerting thought began to form in Luther’s mind about the entire Catholic approach to God: “Who knows whether it is so?”

An Academic Challenge

In 1511 Luther was transferred to a small monastery in Wittenberg, Germany. Here he would serve under a wise priest named Johann von Staupitz. This man seemed to understand something about grace, and Martin’s quest for peace with God.

Discerning that the young monk needed to get his eyes off himself and onto the Scriptures, he assigned Martin the task of serving as professor of the Bible at the University of Wittenberg. Luther became a Bible teacher, which meant he must first become a student of the Scriptures. As he immersed himself in the Bible, his razor–sharp mind quickly began to see the vast disparity between what he had been taught and what the early Church believed. Martin Luther was on his way to becoming an evangelical.

A Life–Changing Discovery

In time Luther discovered the simple truth that would forever change history and shake the mighty Catholic Church to its foundations: “The just shall live by faith” (Habakkuk 2:4, Romans 1:17, Galatians 3:11, and Hebrews 10:38). He began to see that salvation was not a prize to be earned by long prayers and self–abuse; it is a free gift provided through the Cross and resurrection of Jesus and received by faith.

Of course, the doctrine of justification by faith is not some hidden esoteric teaching requiring genius to see it; it is plainly spelled out in the Scriptures. But because the Church in those dark days was so neglectful of the Bible, they had simply gone on century after century believing and preaching the exact opposite of what the Bible actually teaches, insisting upon a complicated formula of salvation through sacraments and various church ordinances. As Luther gained popularity they attempted to prove him wrong by asking how he could possibly suggest that all the leaders of the Church had been in error for the last thousand years, and he, a solitary little monk, was right! Somehow it never occurred to them to check the Scriptures.

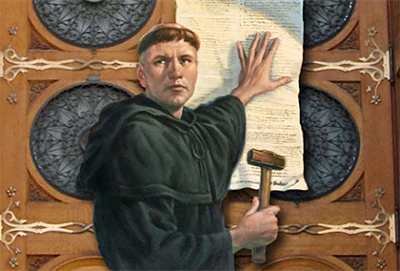

The Protest

Luther’s historic break from the Catholic Church came as a result of a campaign of the pope to raise revenue for the Church through the sale of indulgences. Current church thought was that even the best of Christians must suffer in purgatory after death for perhaps thousands of years while their sins were burned out of them.

However, it was thought that the pope had the authority to somehow dispense with centuries or even millennia of such terrible anguish with a simple letter of indulgence. “Time off” was granted for the viewing of sacred relics, such as a dead saint’s bones or even a tooth, but especially popular with the Vatican were the indulgences granted for financial donations given toward favorite projects.

Johann Tetzel, appointed by the pope as seller of indulgences to Germany had even come up with a jingle to remind the peasants of the power of the indulgence: “As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from Purgatory springs.”

In 1517, Tetzel came near Wittenberg and began to sell indulgences. In this latest sale, the pope outdid himself, promising not only the “plenary and perfect remission of all sins” for the buyers, but also the ability to purchase complete forgiveness for their dead loved ones. When his own parishioners began to grab up these spiritual bargains, Luther exploded.

By now he saw clearly that forgiveness was a matter between the individual and Christ. The Church could proclaim forgiveness through Jesus but could not make it happen and certainly could not sell it!

(http://wrf500wittenberg.org/#event)

Luther responded by writing a blistering article with 95 bullet points, or theses, attacking the sale of indulgences and the Church’s motives behind this practice. He posted the article, written in Latin, on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg, which was a common practice for those wanting scholarly debate over religious points of controversy. Luther had no idea what a storm that little article would unleash.

Preeminent among Martin Luther’s vast array of gifts was his ability to write. He wrote with deep insight, humor, sarcasm, and by now, a solid grasp of the Scriptures. His keen mind and ready pen poured forth a torrent of eloquence, exposing the greed and folly of the Church.

The article was so radioactive that it was soon published and spread all over Germany. Much like the tale of The Emperor’s New Clothes, Luther exposed the spiritual nakedness of the Church, and Germans by the thousands, who had always resented the Church’s autocratic ways and financial demands, began nodding in assent. What historians now call The Reformation was on!

It didn’t take long for the Vatican to hear about this new heresy. They responded by a combination of threats and attempts to defend the indefensible. But the proverbial genie was out of the bottle, and there was no way the Pope and all his cohorts could stuff it back. Luther was eventually excommunicated.

But by the time the spiritual death–certificate arrived, Luther was completely unimpressed, throwing it in the fire. In a written response to being severed from the Church he had once loved and served, Luther wrote caustically:

This condemns me from its own word without any proof from Scripture, whereas I back up all my assertions from the Bible. I ask thee, ignorant Antichrist, does thou think that with thy naked words thou canst prevail against the armor of Scripture? …and as they excommunicated me for the sacrilege of heresy, so I excommunicate them in the name of the sacred truth of God. Christ will judge whose excommunication will stand. Amen.

A Man of Courage

It took incredible courage for Luther to take the stand he did. The Catholic Church had the power to put heretics to death, and it was more than willing to use that power. In the first years of his protest Luther lived with the thought that he probably would soon be burned at the stake. Somehow this didn’t slow him down in the least from writing scathing articles and books denouncing the teachings and hypocrisy of the Church. Amazingly, by the providence of God, he was not martyred.

Luther lived out his days and finally passed away at the age of 62 from a heart attack. Within ten years of his public attack upon the Church, the vast majority of northern Germany had left Catholicism for some form of Protestantism.

Luther left behind two great treasures for the believers. For the body of Christ at large he restored to them the truth Paul had asserted so long ago: “…having been justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ” (Romans 5:1). And to his fellow Germans he gave them another priceless gift — he translated the entire Bible into the language of the people. Until then only the Latin scholars could read the Scriptures, but now farmers and bakers and bankers and housewives could read the doctrines of grace for themselves.

A Man of Excesses

Without question Martin Luther was a mighty instrument in the hands of God. He certainly had his flaws, and he wore them on his sleeve. He could be harsh, crude, sarcastic, extremist, impatient, and often grumpy. He was also guilty of pressing the doctrines of grace to extremes until they became nearly heretical. For instance, in his determination to show that salvation is “all of grace” he wrote:

Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death, and the world. We will commit sins while we are here, for this life is not a place where justice resides…No sin can separate us from Him, even if we were to kill or commit adultery thousands of times each day…

This is a far cry from the apostle Paul’s attitude about Christians who sin, when he asked, “Shall we continue in sin that grace may abound? Certainly not! How shall we who died to sin live any longer in it?” (Romans 6:1, 2). John declares, “He who says, ‘I know Him,’ and does not keep His commandments, is a liar, and the truth is not in him” (1 John 2:4). Paul warns that adulterers “will not inherit the kingdom of God.” So it is hard to see how someone who committed adultery thousands of times each day (if that were possible) would have any right to enter heaven at the conclusion of his lecherous life.

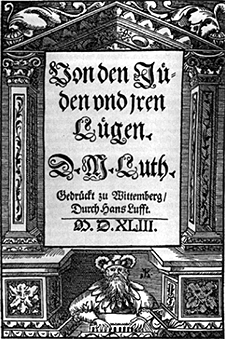

An Anti–Semite

One of the most disgusting of Luther’s many excesses and errors was his attacks on the Jews. In his early days, he was tolerant of the Jews and reminded his followers that Jesus was a Jew. He encouraged Christians to treat the Jews kindly in the hope that some might come to Christ.

But in his later years Luther became disillusioned about the prospect of Jews turning to Jesus. Despite the phenomenal success of the Reformation, few Jews had embraced Christianity, either the Catholic version or his Reformation version. As an older man, Martin Luther concluded that the Jews were simply too hard–hearted to be saved by Christ, and that they had thus been eternally rejected by God.

Once convinced of this, Luther’s attitude toward the Jews changed dramatically. He unleashed his anger at the Jewish people in a booklet entitled, On the Jews and Their Lies. It was horrible. In it Luther roundly condemned the Jews for not converting to Christ and called them a “base, whoring people, that is, no people of God…full of the devil’s feces…which they wallow in like swine.”

Worse still he advised Christians to persecute them vigorously. They were urged to burn all Jewish schools and synagogues, confiscate all Jewish literature, prohibit rabbis to teach on pain of death, deny Jews safe conduct on the roads, and appropriate their money to be used to support Christianity.

Luther’s encouragement of violence toward the Jews is so horrific it can hardly be believed. How in the world could a man so powerfully used of God to wake the Church from her slumber be so filled with hatred?

The truth is, Martin Luther did not improve with age. As he became older his success, fame, and popularity seemed to exacerbate his tendencies toward grumpiness, crudeness and anger. He became the proverbial grumpy old curmudgeon. When ordinary, unknown men grow into curmudgeons nobody pays too much attention, save for perhaps their children. But when a world–famous theologian allows anger, frustration and irritability to saturate his writings, it becomes a big deal.

It is almost humorous to see how many modern–day ministers try to excuse Luther for his excesses in this area. “He was a man of his times,” they say. Or “he was given to polemics,” or “others were saying worse things,” or “his many illnesses were making him irritable.” One writer piously states, “Let us neither excuse him nor condemn him.”

The truth is, there is no excuse for Luther’s outrageous and violent outbursts against the Jews, and without a doubt many Jews suffered terribly as a result of his anti–Jewish writings. We can and should condemn his terrible outbursts against the Jews.

Adolf Hitler admired Luther and acknowledged him as one of Germany’s great champions. In Hitler’s own persecution of the Jews, he clearly took a page from Luther’s playbook in saying, “by defending myself against the Jew, I am fighting for the work of the Lord.”

Conclusion

All of this is puzzling to us. We all recognize that no one is perfect, but we prefer our leaders and heroes to at least have minor flaws and warts — not monstrous ones that bring damage and pain to people.

Yet imperfection has never stopped God from making use of His chosen instruments. Luther was precisely what the times called for. He was fearless in the face of threats, tireless in his proclamation of the truth of salvation by grace, and brilliant in his written exposes of the immoral, corrupt and disingenuous Church of his day.

Unlike most monks and priests in those dark times, he actually read the Bible and held unflinchingly to the truths he discovered. Some things he got terribly wrong but the main thing he got very much right — we are indeed saved by grace through faith. Above all else, Martin Luther was a man who took God seriously.

Such a simple thought — who would believe it could start a revolution: “The just shall live by faith.”