October 31, 2017

Celebrating the 500th Anniversary of the Reformation

By Dr. Timothy J. Demy

Dr. Timothy J. Demy is a professor of ethics at the United States Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island.

He is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary (Th.D.) and the University of Cambridge (Ph.D.). He is the author of numerous books on history, theology and current events.

Prior to his faculty appointment, he served 27 years as a U.S. Navy Chaplain.

The Protestant Reformation swept across Europe like a theological tsunami affecting every social, political, and religious institution in existence in the West. And its effects remain a part of western culture and permeate it 500 years later. In its wake a new world was created.

No other event in the then almost 1500–year history of Christianity had been so tumultuous. And like a tsunami, there was more than a single theological wave moving over Europe and crashing against the established Catholic Church. The Reformation consisted of several movements of renewal and reform, even though we usually think of them as one big thing we call the Reformation. It was profound and generated longlasting consequences.

From its inception, advocates, critics, observers, theologians, and historians have called the Reformation many things, among them: a revolution, a religious hurricane, a heresy, an evolutionary process, and a score of other things. Metaphors, analogies, and depictions of it abound. In a sense, many of them are correct or overlap in their description. Few people in the last 500 years have denied the Reformation’s significance and its lasting influence.

The Reformation was indeed, many things. It was social. It was political. It was economic. It was cultural. But fundamentally and at its core, it was theological.

The Beginnings

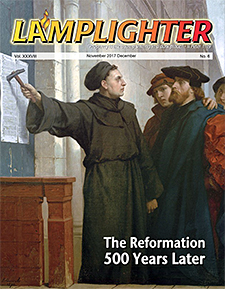

Popular understanding of the Reformation dates to All Souls’ Eve, October 31, in the liturgical calendar of the year 1517 and to the actions of a German theologian and university professor named Martin Luther. However, the actions of this monk with a mallet, posting a call for public debate on the door of the church in Wittenberg was not the work of a single individual igniting a firestorm on his own. There had been precursors. Ideas never arise in a vacuum.

Just as a tsunami begins its powerful surge starting far out at sea and miles from the unsuspecting landmass it approaches, so too did the Reformation begin years before Luther’s posting of the infamous “95 Theses.” There long had been growing swells of discontent within Christianity in the West.

The world of medieval Catholic (Latin) Christianity, out of which the Reformation arose, was multifaceted with strengths and weaknesses. In the experiences and views of the Reformers, the latter outweighed the former. For them, Catholicism and Christianity in the West had become an impersonal and ecclesiastical bureaucracy that favored the hierarchy that controlled it at the spiritual and financial expense of the laity.

Some, desiring reform in the Church, believed that it could be accomplished best by remaining within Catholicism. Others, diametrically opposed, argued for withdrawal. And yet others hoped to bring reformation from within, but gradually conceded the necessity of withdrawal. Reform caused multiple responses.

Reform Efforts

For a couple of hundred years, at least, there had been a growing concern regarding papal power. For example, this concern had been addressed at the 1415 Council of Constance in which the council declared in a document called Sacrosancta that the authority of a general council was superior to the authority of the Pope. The Pope abrogated the document but the concern remained.

There also were some attempts for reform within individual geographic and ecclesiastical regions as well as within some monasteries, but it remained sporadic and uncoordinated. One positive development in the years before the Reformation was the rise of lay devotion communities that emphasized spirituality and holy living in daily life for everyone. Within this movement were individuals such as Thomas à Kempis (1380–1471), whose devotional book, The Imitation of Christ (1418–1427) became and remains very popular.

A corollary to this movement was an emphasis on contemplation and prayer (often resulting in mysticism). Martin Luther owed much to the German mystic Johannes Tauler (ca. 1300-1361) and the work Theologia Germanica (late 1300s).

Two strong pre–Reformation movements that challenged the ecclesiastical power and hierarchy of the Catholic Church as well as fundamental doctrines of Catholicism were the Lollards in England and the Hussites in Bohemia. The former, inspired by John Wycliffe (1320–1384) and the latter by John Hus (d. 1415), gave strong criticism of the practices and theology of Catholicism, including the Mass and devotion to saints.

Further, Wycliffe maintained that Scripture interpreted in a literal sense should be normative practice and the sole criterion for belief and the Christian life. To this end, he and his associates translated the Bible into English so that it could be widely read and studied, rather than having to rely on hearing it read in Latin in church by a priest.

It was in this same spirit that English Bible translator William Tyndale would declare 100 years later (in the English of his day), “I defie the Pope and all his lawes. If God spare my life, ere many yeares I wyl cause a boy that driveth the plough to know more of the Scripture, than he doust.” Although Tyndale was executed in 1536 in Belgium, much of his work influenced the King James Version (1611) of the Bible.

Intellectual Trends and Social Changes

Within the intellectual life of the pre–Reformation world the currents were changing. For many years, an intellectual framework known as Realism (scholasticism) had prevailed as found in the work of one of its foremost proponents, Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the author of the great theological treatise Summa Theologica. These thinkers wanted to marry Greek philosophy, logic and thought with Christian theology and the teachings of the Church.

In opposition to this view there arose the school of thought and counter–framework known as Nominalism. Nominalists led by people such as Duns Scotus (d. 1308), argued that reason and logic were insufficient for the truths of revelation. These, he argued, depended ultimately on the faith of the believer.

Debate such as this continued in the pre–Reformation years and, in part, was possible because of the rise of Christian Humanism during the Renaissance that focused on the rediscovery and growing accessibility of ancient texts of classical authors and the early Church Fathers. The desire and ability to read these authors in Greek in which they were originally written also influenced greatly the study of the New Testament in Greek by Christian Humanists such as Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466–1536).

Social changes such as the rise of schools and universities, the growth of towns and cities, and the invention of the printing press significantly helped in increasing literacy and spreading new ideas through wide dissemination of books and pamphlets.

Political Trends

As theological protests and calls for reform increased and became widespread, the Church could only effectively eliminate dissent by relying on the growing power of secular rulers and these princes and authorities had to be persuaded that the action was necessary. The political power of the papacy and Catholicism was weakening.

Throughout the Reformation era, as the core theological ideas of the movement spread geographically, the tug–of–war political power contest between the Catholic Church and the local magistrates, princes, kings, and queens also ensued. The theological debates and struggles were accompanied by political and social struggles.

Technological Developments

The advent of the printing press in the years before the Reformation enabled widespread dissemination of the Bible and its teachings. It also put the Bible within reach for the average man and woman and in their own language, as illustrated by Luther’s translation of the Bible into German (1522 and 1534) and the work of others to create the influential Geneva Bible (1557 and 1560) that was printed in English and was a precursor to the King James Version (1611).

The ability to disseminate the biblical text widely and relatively inexpensively compared to handwritten copies of it enabled the reading and study of the Bible to flourish and spread. An example of this is the fact that in addition to the introduction of chapter and verse markers, the Geneva Bible had study notes added to the margins of the text so that readers could study the text individually or in small groups.

The foremost idea and most important outcome of the Reformation was the reaffirmation of the central idea of Christianity — the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

The Impact of the Reformation

Corresponding to the revitalized centrality of the Gospel in Christian faith and practice was belief in the right of every individual to interpret the biblical text and the Christian faith rather than have it presented from a centralized authority. Luther’s radical idea of the “priesthood of all believers” emphasized the ability, the right, and the legitimacy of individuals to engage in intimate knowledge of, communication with, and relationship with God. This had spiritual and social consequences.

Spiritually and theologically it meant that the individual Christian had the power and responsibility to nurture their own spiritual lives. This built on the earlier Renaissance shift in the understanding of humanity and individual responsibility to God as men and women created by God in His image.

One consequence of this shift in the understanding of humans and their relationship with God was a change in the medieval concept of spiritual vocation whereby those who entered the priesthood or a monastery or convent were thought to be more important spiritually than others.

Luther’s emphasis on the priesthood of all believers meant that there was to be no dichotomy between the spiritual world and the world of daily life. The work of the farmer, baker, shipwright, seamstress, carpenter, or teacher had equal significance to the cleric, monk, or nun.

Indeed, English reformer William Tyndale declared that washing dishes and preaching the Word of God were both pleasing to God and without essential difference. (Out of this model and idea of the 1530s came what has been called “the Protestant work ethic.” It was that but it was much more — it was a part of a comprehensive Christian worldview.)

Five Key Doctrines

The theology of the Reformation crystallized around five central doctrines. In the nearly 1500 years since the New Testament era and founding of the Church, much had occurred in the development of the doctrine and practices of the church — some of it biblical and some of it not biblical. Out of the morass of medieval theology, spiritual practices, and ecclesiastical power, the Reformers sought to reaffirm the central theological ideas and “to contend for the faith that was delivered to the saints once for all” (Jude 3, HCSB).

In so doing, they emphasized five beliefs that were at the core of the Reformation. Called “solas” from the Latin word for “alone,” these biblical ideas permeated the Reformation. A systematized formal list of these five ideas did not arise until after the Reformation but each of the ideas was present during it and some of the ideas such as Sola Gratia and Sola Fide were utilized together by the Reformers:

1 Sola Scriptura — This phrase means “Scripture alone,” and was an idea and emphasis that was quickly applied. With respect to salvation, the Bible provides the content of salvation. The Bible was understood to be the final authority in matters of doctrine and practice rather than Cardinals, Councils, or the Church. It means also that Scripture interprets Scripture.

A central idea of the Reformation was the belief that the Bible was capable of being understood by all Christian believers and that every believer has the right to interpret the Bible for himself or herself and to have every interpretation taken seriously — a very democratic idea.

2 Sola Gratia — This phrase means “grace alone” and emphasized the biblical view that salvation is solely by grace — it is the means of salvation. Salvation does not come through works or because of the spirituality of other Christians who acquired extra grace or excess grace through their works.

This latter idea was part of the idea of a “treasury of merit” that accumulated in heaven because of the holiness of saints and from which people on earth could draw through the purchase of indulgences that would then benefit them or their living and deceased loved ones. It was the selling of such indulgences by papacy (in part to fund the building of St. Peter’s basilica in Rome) that was the tipping point for Luther.

3 Sola Fide — This phrase means “faith alone” and reiterated a central teaching in the New Testament, especially the book of Romans. The appropriation of salvation comes through faith alone. Coupled with Sola Gratia, it affirmed that salvation comes as an act and gift of God to individuals solely because of their faith in the finished work of Jesus Christ on the cross. Nothing is or can be added to such faith to gain eternal life.

Sola Fide and Sola Gratia are affirmations of Paul’s words in Ephesians 2:8–9: “For you are saved by grace through faith, and this is not from yourselves; it is God’s gift–not from works, so that no one can boast.”

4 Solus Christus — “Christ alone” offers access to God the Father based upon His substitutionary death on the cross. Christ alone is the basis of a person’s salvation. Jesus Christ is the sole mediator between God and humans. Paul declared in 1 Timothy 2:5–6: “For there is one God and one mediator between God and humanity, Christ Jesus, Himself human, who gave Himself — a ransom for all, a testimony at the proper time” (HCSB). The Reformers affirmed this wholeheartedly.

5 Soli Deo Gloria — is a phrase meaning “glory to God alone.” With respect to salvation, glory to God alone is the reason a person strives to live a life pleasing to God.

With this phrase, the Reformers meant that all of life and every aspect of life was meant to bring glory to God. As noted above, such an idea broadened the Medieval Church’s concept of vocation (vocatio) such that there was no spiritual distinction between clergy and laity.

(biography.com)

Five Historical Traditions

The five doctrines noted above formed the core of Reformation theology, a theology that enabled every person to directly enter into a personal relationship with God through the sacrificial death of Jesus Christ on the Cross. As the theological tsunami of the Reformation spread across Europe and the British Isles, it was shaped by the culture, people, and leaders of particular areas and in conjunction with history of Christianity to date in those areas.

There was turmoil, conflict and dissent. The historical traditions developed against the backdrop of political power plays between princes and cardinals, emperors and popes, and persistent greater threats such as the military and religious presence of the Ottoman Empire pushing inwardly in Europe. And yet, the Reformation spread rapidly.

Out of the unity of the five doctrines there arose diversity of expression leading to five major historical traditions within the Reformation. If one asks today “why are there so many denominations in Protestantism,” the answer rests in part on the five historical traditions of the Reformation.

Why are there Lutherans?— the Reformation. Why are there Presbyterians?— the Reformation. Why are there Baptists?— the Reformation. Why are there Anglicans and Episcopalians?— the Reformation. Why are there Mennonites and Quakers?— the Reformation. Today within each of the five strands or traditions there are many groups, each with its own history and theological emphases, but all of them are rooted in the Reformation.

The Lutherans

Apart from precursors of the Reformation such as John Wycliffe, John Hus, and others leading up to the 16th Century, the first major tradition of the Reformation is that of the Lutheranism that arose from Luther’s historic call for reform. Martin Luther (1483–1546) was the undisputed leader of it and was assisted and succeeded by Philip Melanchthon (1497–1560).

It was a German movement and was firmly rooted and established within twenty years of Luther’s death. Like other traditions of the Reformation, one byproduct of the movement was an increased appreciation for and development of access to education for many people, regardless of their social status.

The Calvinists

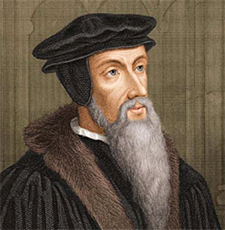

The second major tradition was that of the Swiss Reformation and the ensuing Reformed Tradition. In Switzerland the leading reformer was the German–Swiss leader Ulrich Zwingli (1484–1531). In the French regions of Switzerland (and in France) the Reformation leaders were John Calvin (1509–1564) and Theodore Beza (1519–1605).

The ideas of these reformers, collectively termed Calvinism, spread throughout France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and into England and Scotland. Interacting with the currents of reform locally in these regions, there was enormous dissemination and growth in what would emerge as Presbyterianism and the larger Reformed Tradition. This is especially true of the work of John Knox (c. 1505–1572), known as the “Reformer of Scotland.”

The Anglicans

The third Reformation tradition was that of the English Reformation and the Anglican tradition. Though it began under the reign of Henry VIII (1491–1547) and his desire for a divorce that the papacy would not sanction, the break with Rome became in time a distinct strand of the Protestant Reformation. Henry VIII essentially made the Church in England, the Church of England but ideas of reform soon followed.

For more than 100 years there was a religious tug–of–war and a military civil war in England as Catholic and Anglican monarchs acceded to the throne, but in the end Anglicanism prevailed and spread throughout the world as the British empire came to dominate global activity.

When the American colonies broke with the British and gained independence, the Anglican Church in the new United States became the Episcopal Church.

The Baptists

The fourth tradition was the Baptist tradition. Some historians see it arising on the European continent and as an offshoot of people who had disagreement with the work of the GermanSwiss leader Ulrich Zwingli and some of his theology.

Other historians acknowledge the continental influence but believe today’s Baptists are more the product of the English Puritan movement of the 17th Century that gave rise to English Baptists rather than the 16th Century Mennonite tradition. Origins aside, no one disputes the emphasis on believers’ baptism by immersion and the spread of Baptists, especially in the English–speaking world.

The Free Churches

The fifth and final tradition is what is sometimes termed the “Radical Reformation.” Whereas the Reformed, Lutheran and Anglican traditions sought to maintain much of the social–political world of their day and saw some unity between the Church and the State (and is thus termed the “Magisterial Reformation”), the Radical Reformation sought a full break between the realms of the Church and the State (thus the term “Free Churches” is often used).

Notable within the Radical Reformation are the Anabaptists (a name given by opponents) such as Menno Simons (1496– 1561), the Society of Friends (Quakers) founded by George Fox (1624–1691), and the more violent and extreme Thomas Müntzer (c. 1490–1525). Eventually dissenters within the Anglican tradition would combine with some Baptists and Anabaptists and there would emerge the Congregational churches that were part of much of the American Puritan experience.

Summary

There was complexity in these five traditions but more important, there was unity in the overarching belief that reform was necessary. The Protestant Reformers differed on aspects of theology, church government, and the relationship of the Church to the State but they did not differ on the need to change the existing church. They had social and cultural differences but shared a common theological desire.

A Comprehensive Worldview

The significance of the Reformation rests not only in what it accomplished theologically, but in what it accomplished in the broader western culture as well. It provided a biblical framework for many of the ideas of the next 500 years, enabling Christians to develop a comprehensive worldview.

Whether one looks at science, education, economics, art, political philosophy or music, there is the imprint of the Protestant Reformation. Because the Bible was being read and interpreted in a new way the biblical text was understood to be foundational to every discipline and every area of life.

- Thus, the medieval prohibitions against usury (lending money) gave way to fuller understandings of the biblical passages dealing with that subject and the rise of capitalism emerged. There is a direct link between Calvinism and economic entrepreneurialism.

- Hymns and music were written for congregations to sing in their own language just as they read the Bible in their own language.

- The idea of kings and queens ruling by divine right gave way to the rise of democratic ideas of government.

- The Reformation idea of “power to the people” with respect to reading and interpreting the Bible had many consequences — diversity of interpretations, increase in and support of literacy, education and Bible translation.

The theological tsunami of the Protestant Reformation changed the world. What began in the hearts of individual women and men 500 years ago was soon applied with their hands as they literally carried the Gospel of Jesus Christ around the globe and applied it to daily life. It was theological at its core, with ideological ramifications affecting every area of culture and society.

In the 62nd of Luther’s 95 theses, he declared: “The true treasure of the Church is the most holy Gospel of the glory and grace of God.” In making this declaration Martin Luther was reaffirming the words of the Apostle Paul written in his letter to the Romans (1:16–17): “For I am not ashamed of the gospel, for it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes, to the Jew first and also to the Greek. For in it the righteousness of God is revealed from faith for faith, as it is written, ‘The righteous shall live by faith.'” (ESV).

This passage of Scripture had been instrumental in Luther’s spiritual awakening, his “reformatory breakthrough” as he called it, and it remained so throughout his life.

Conclusion

The Protestant reformers were bold. They challenged more than a thousand years of history and tradition. They believed the Bible and the truths contained in it, and they demonstrated daily the power of the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the truths of the Bible to change lives and history.

The Protestant Reformers gave us a legacy, and they challenge us to believe and act daily upon the truths we read in the Bible and to apply those truths in every area of our lives — private and public. Ideas have consequences!

Recommended Reading

Two great books that provide excellent overviews of the Reformation and its importance are:

1) John D. Hannah, The Kregel Pictorial Guide to Church History Volume 4— The Reformation of the Church (The Early Modern Period) A.D. 1500-1650 (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 2009).

2) Stephen J. Nichols, The Reformation: How a Monk and a Mallet Changed the World (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2017).