The Feasts of Israel

Do they have prophetic significance?

“Let no one act as your judge in regard to food or drink or in respect to a festival or a new moon or a Sabbath day things which are a mere shadow of what is to come; but the substance belongs to Christ.” Colossians 2:16-17 (NASB)

This statement by the Apostle Paul refers to the Jewish Feasts as a “mere shadow” of things to come, the substance of them being found in Yeshua, the Messiah. What Paul is saying here is that the feasts were prophetic types, or symbols, that pointed to the Messiah and which would be fulfilled in Him.

Before we pursue that point to see how the feasts were fulfilled in Jesus, let’s first of all familiarize ourselves with the feasts.

Origin and Timing of the Feasts

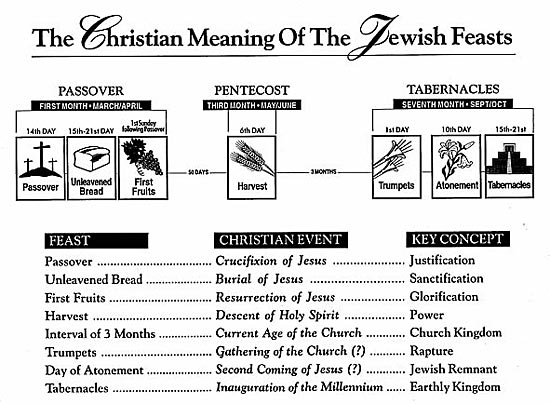

The feasts were a part of the Mosaic Law that was given to the Children of Israel by God through Moses (Exodus 12; 23:14-17; Leviticus 23; Numbers 28 & 29; and Deuteronomy 16). The Jewish nation was commanded by God to celebrate seven feasts over a seven month period of time, beginning in the spring of the year and continuing through the fall. You will find the timing and sequence of these feasts illustrated on the chart below.

As you study the chart, notice that the feasts fall into three clusters. The first three feasts Passover, Unleavened Bread, and First Fruits occur in rapid succession in the spring of the year over a period of eight days. They came to be referred to collectively as “Passover.”

The fourth feast, Harvest, occurs fifty days later at the beginning of the summer. By New Testament times this feast had come to be known by its Greek name, Pentecost, a word meaning fifty.

The last three feasts Trumpets, Atonement, and Tabernacles extend over a period of twenty-one days in the fall of the year. They came to be known collectively as “Tabernacles.”

The Nature of the Feasts

Some of the feasts were related primarily to the agricultural cycle. The feast of First Fruits was a time for the presentation to God of the first fruits of the barley harvest. The feast of Harvest was a celebration of the wheat harvest. And the feast of Tabernacles was in part a time of thanksgiving for the harvest of olives, dates, and figs.

Most of the feasts were related to past historical events. Passover, of course, celebrated the salvation the Jews experienced when the angel of death passed over the Jewish houses that were marked with the blood of a lamb. Unleavened Bread was a reminder of the swift departure from Egypt so swift that they had no time to put leaven into their bread.

Although the feasts of Harvest and Tabernacles were related to the agricultural cycle, they both had historical significance as well. The Jews believed that it was on the feast day of Harvest that God gave the Law to Moses on Mt. Sinai. And Tabernacles was a yearly reminder of God’s protective care as the Children of Israel tabernacled in the wilderness for forty years.

The Spiritual Significance of the Feasts

All the feasts were related to the spiritual life of the people. Passover served as a reminder that there is no atonement for sin apart from the shedding of blood. Unleavened Bread was a reminder of God’s call on their lives to be a people set apart to holiness. Leaven was a symbol of sin. They were to be unleavened that is, holy before the nations as a witness of God.

The feast of First Fruits was a call to consider their priorities, to make certain they were putting God first in their lives. Harvest was a reminder that God is the source of all blessings.

The solemn assembly day of Trumpets was a reminder of the need for constant, ongoing repentance. The Day of Atonement was also a solemn assembly day a day of rest and introspection. It was a reminder of God’s promise to send a Messiah whose blood would cover the demands of the Law with the mercy of God.

In sharp contrast to Trumpets and Atonement, Tabernacles was a joyous celebration of God’s faithfulness, even when the Children of Israel were unfaithful.

The Prophetic Significance of the Feasts

What the Jewish people did not seem to realize is that all of the feasts were also symbolic types. In other words, they were prophetic in nature, each one pointing in a unique way to some aspect of the life and work of the promised Messiah.

1) Passover — Pointed to the Messiah as our passover lamb whose blood would be shed for our sins. Jesus was crucified on the day of preparation for the Passover, at the same time that the lambs were being slaughtered for the Passover meal that evening.

2) Unleavened Bread — Pointed to the Messiah’s sinless life, making Him the perfect sacrifice for our sins. Jesus’ body was in the grave during the first days of this feast, like a kernel of wheat planted and waiting to burst forth as the bread of life.

3) First Fruits — Pointed to the Messiah’s resurrection as the first fruits of the righteous. Jesus was resurrected on this very day, which is one of the reasons that Paul refers to him in I Corinthians 15:20 as the “first fruits from the dead.”

4) Harvest or Pentecost — (Called Shavuot today.) Pointed to the great harvest of souls, both Jew and Gentile, that would come into the kingdom of God during the Church Age. The Church was actually established on this day when the Messiah poured out the Holy Spirit and 3,000 souls responded to Peter’s first proclamation of the Gospel.

The long interval of three months between Harvest and Trumpets pointed to the current Church Age, a period of time that was kept as a mystery to the Hebrew prophets in Old Testament times.

That leaves us with the three fall feasts which are yet to be fulfilled in the life and work of the Messiah. Because Jesus literally fulfilled the first four feasts and did so on the actual feast days, I think it is safe to assume that the last three will also be fulfilled and that their fulfillment will occur on the actual feast days. We cannot be certain how they will be fulfilled, but my guess is that they most likely have the following prophetic implications:

5) Trumpets — (Called Rosh Hashana today.) Points to the Rapture when the Messiah will appear in the heavens as a Bridegroom coming for His bride, the Church. The Rapture is always associated in Scripture with the blowing of a loud trumpet (I Thessalonians 4:13-18 and I Corinthians 15:52)

6) Atonement — (Called Yom Kippur today.) Points to the day of the Second Coming of Jesus when He will return to earth. That will be the day of atonement for the Jewish remnant when they “look upon Him whom they have pierced,” repent of their sins, and receive Him as their Messiah (Zechariah 12:10 and Romans 11:1-6, 25-36).

7) Tabernacles — (Called Sukkot today.) Points to the Lord’s promise that He will once again tabernacle with His people when He returns to reign over all the world from Jerusalem (Micah 4:1-7).

The Week of Millenniums

One final note about the feasts. Six of them the first six are related to man’s sin and struggle to exist. The last feast, Tabernacles, is related to rest. It is the most joyous feast of the year. It looks to the past in celebration of God’s faithfulness in the wilderness. It looks to the present in celebration of the completion of the hard labor of the agricultural cycle. And it looks to the future in celebration of God’s promise to return to this earth and provide the world with rest in the form of peace, righteousness and justice.

The seven feasts thus parallel what I call the “rhythm of God” that was established during the week of creation namely, six days of work followed by one day of rest.

This rhythm is repeated over and over in the Scriptures, as illustrated in the chart below.

A Summary of the Weeks of Scripture

| The Week | Length | Description | Scripture |

| 1) Week of Days | 7 days | God’s basic pattern. Six days of toil followed by a Sabbath day of rest. | Gen. 1:31-2:3; Ex. 31:12-17 |

| 2) Week of Weeks | 49 days | The period of time between the feast of First Fruits and the feast of Pentecost. | Deut. 16:9-12; Lev. 23:15-16 |

| 3) Week of Months | 7 months | The seven months of the Jewis religious calender which contain all seven of the Jewish feasts. | Deut. 16; Lev. 23 |

| 4) Week Years | 7 years | The Israelites were commanded to work the land for six years and then give the land a sabbath rest every seventh year. | Lev. 25:1-7 |

| 5) Week of Weeks of Years | 49 years | The period of time between each celebration of the Year of Jubilee. | Lev. 25:8-17 |

| 6) Week of Decades | 70 years | The life span alotted to Man. | Ps. 90:10 |

| 7) Week of Weeks of Decades | 490 years | The period of time revealed to Daniel during which God will work through the Jews to fulfill His purposes in history. | Dan. 9:24-27 |

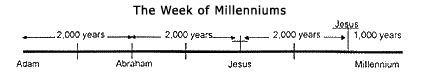

Because God’s division of time into sevens, or weeks, so thoroughly permeates the Scriptures, the Jewish Rabbis concluded before the time of Jesus that human history would extend over a “Week of Millenniums,” or for a period of 7,000 years.

According to the view most frequently expressed in the Talmud, there would be 6,000 years of human toil and strife followed by 1,000 years of peace. This Millennial Sabbath would be the period of the Messianic kingdom during which time the Messiah would reign in person over all the world from Jerusalem (Isaiah 24:21-23).

In other words, the Jews had concluded long before the book of Revelation was written that the Lord’s reign on earth would last a thousand years. Revelation 20 confirmed this deduction by stating six times that the reign would last a thousand years.

The concept of the Millennium in the book of Revelation is therefore nothing new. The concept is rooted in the creation week of Genesis. It is reaffirmed in the week of feasts of Israel six feasts related to sin and toil leading up to a sabbath feast of rest.

As you can see from the chart below, we are near the end of the 6,000 years which the Jewish Rabbis believed would usher in the Millennial kingdom. We are standing on the threshold of the Sabbath Millennium. Yeshua is coming soon!

For Deeper Study About the Feasts

Richard Booker observes in a book concerning spiritual meanings of the feasts for the Christian life that for 1,500 years, the Jewish people learned about God through “visual aids” like the feasts. As he puts it, “Their religious laws and rituals taught them how to know God and walk with Him on a daily basis.

But Booker stresses that these were only aids. The time came when the Jews were to put away these physical symbols and enter into the spiritual reality which they portrayed. The transition from the physical to the spiritual was provided for them through the person and work of Jesus, their Messiah and Savior of the world.

As Booker puts it, “Jesus was God’s ultimate visual aid.” Jesus Himself emphasized this when He said, “Anyone who has seen Me, has seen the Father” (John 14:9).

The Jewish rituals were only temporary visual aids. God used them as object lessons to teach the Jewish people about their coming Messiah. We no longer need these rituals to show us the way to God.

But Booker observes: “This does not mean, however, that these Hebrew visual aids are no longer valuable to us. They still are very useful in helping us to better understand how to know God and walk with Him through a personal relationship with Jesus.”

Which is why Booker wrote the book “I wrote this book to help people learn how to encounter God in such a way that they will walk in His divine peace, power, and rest.”

Why the Jewish Feasts Move Around on the Calendar

One of the first things you will probably notice when studying any chart of the Jewish Feasts is that they do not fall on specified dates according to the Gregorian calendar that is used in the Western world. The reason is that the Gregorian calendar (adopted in 1582 during the reign of Pope Gregory XIII) is a solar one that is related to the earth’s revolution around the sun. The Jews, in contrast, use a modified lunar calendar, or what might be called a lunar/solar calendar.

A year on the Gregorian calendar runs 365 days. But since it takes approximately 365 days for the earth to make a complete circle around the sun, an extra day is added in February every four years, making a Leap Year of 366 days.

The Jewish calendar is based upon the movement of the moon around the earth. A full circle takes about 29 days. Thus, twelve of these lunar months add up to 354 days in a year. So, a solar year is 11 days longer than a lunar year.

If the Jews followed a strict lunar calendar, as the Muslims do, the feasts would migrate completely around the calendar (as the Muslim feast of Ramadan does.) But the Jews could not tolerate this since three of their feasts are related directly to the agricultural cycle. Therefore, they devised a method of modifying their lunar calendar to bring it in line with the solar year. They did this by adding an extra month of 29 days about every three years (7 times in 19 years). This month is called the intercalary month.

That’s the reason that the feast of Passover, for example, can occur in either March or April. The feast migrates backward on the Gregorian calendar for three years and then is propelled forward 29 days when the intercalary month is added. Passover always falls on Nisan 14 on the Jewish calendar, but that date moves around on the Gregorian calendar as illustrated below.

Dates of Passover 1992-1995

| Year | Jewish Date | Gregorian Date |

| 1992 | Nisan 14 | Sunday, April 17 |

| 1993 | Nisan 14 | Monday, April 6 |

| 1994 | Nisan 14 | Saturday, March 26 |

| (Intercalary month added) | (Intercalary month added) | (Intercalary month added) |

| 1995 | Nisan 14 | Sunday, April 14 |

In 1997, for example, an intercalary month was added. Without it, Passover would fall on the evening of March 23rd. But with the month added (March 10-April 7), Passover fell on the evening of April 21st.

Another difference between the calendars that should be noted is that the Gregorian day begins at midnight and runs until the next midnight. The Jewish day begins at sundown (approximately 6:00 p.m.) and runs until the next day’s sundown. The Passover meal is celebrated at the beginning of Nisan 14, which would be in the evening.