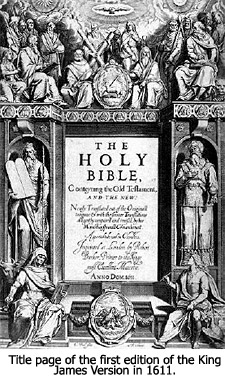

The King James Bible

Celebrating 400 Years

The King James Version of the Bible was published 400 years ago in 1611, and it served the English-speaking world very well during the 250 years of its peak acceptance (1700 to 1950).

It was not really a new and fresh translation of the Scriptures. Rather, it was primarily a revision of previously existing translations. And for that reason, it cannot be fully appreciated apart from a history of the English translations of the Bible.

The Latin Vulgate

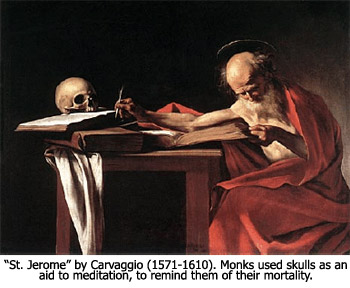

The first point that needs to be made clear is that the Bible used in the Western world for almost 1200 years prior to the King James Version was the Latin Vulgate (vulgate means the Latin that was commonly spoken).1 This translation was produced between 382 and 405 A.D. by Eusebius Hieronymus, better known as St. Jerome (c. 347-420 A.D.).2 He worked from Greek texts to produce his New Testament translation. When translating the Old Testament he resorted to Hebrew texts and is generally regarded as the first to do so. All previous translations of the Old Testament had been based on the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures which was produced in the 3rd Century B.C.3

By the time of the King James Version, Latin had ceased to be the common language of peoples in Western Europe. It was understood primarily by the educated, and Latin Bibles were confined to libraries and churches. The average person was illiterate and had little knowledge of the Bible. Basically, all they knew about Christianity is what the Roman Church taught them, and much of that was thoroughly unbiblical.

The Wycliffe Bible

The story of English translations begins in the 14th Century with an Oxford professor and theologian by the name of John Wycliffe (c. 1328-1384).4 He was a dissident Catholic who produced hand-written translations of the Scriptures in English, all of which were translated from the Latin Vulgate. Here is a sample of his translation in 1380 of John 3:16 —

For god loued so the world; that he gaf his oon bigetun sone, that eche man that bileueth in him perisch not; but haue euerlastynge liif.5

Wycliffe’s efforts to get the Scriptures into the language of the English-speaking peoples enraged the Vatican. The Church fought against the Bible being translated into vernacular languages for fear it would undermine unbiblical traditions like indulgences. The rage of the Vatican was so great, that 40 years after Wycliffe had died, the Pope ordered that his bones be dug up, crushed, and scattered in a river.6 The opposition of the Church throughout this period was, in fact, so virulent that in 1517 seven people were ordered to be burned at the stake for teaching their children to say the Lord’s Prayer in English rather than in Latin.7

Johannes Gutenberg

In the midst of all this struggle to get the Bible into the languages of the people, a profound event occurred that had to represent the perfect timing of God. A German printer and publisher, Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1398-1468), invented a printing press with movable type.8 Significantly, the first thing he printed was a copy of the Latin Vulgate Bible.

Looking back on this development today, it is obvious that God was preparing the way to get His Word into the hands of the common people.

William Tyndale

The next key individual in the effort to produce an English Bible was a remarkable man named William Tyndale (c. 1494- 1536).9 In fact, he ultimately proved to be the most important person in the whole process, as we shall see.

Tyndale was a genius who was fluent in eight languages. He was the leading scholar of Greek at Cambridge University when he decided to translate the New Testament into English. When he could not get the approval of the Church for his project, he moved to the Continent and took up residence in Germany where he finished his translation in 1525. Four years later he began translating the Old Testament.

Tyndale’s translations were the first in English to be based directly on Greek and Hebrew texts. His English New Testament was the first to be printed, making it available for widespread distribution. Copies were smuggled into England, resulting in Tyndale being declared a heretic. He further enraged English authorities when he wrote and published an attack in 1530 on King Henry VIII’s divorce.

In 1535 Tyndale was betrayed by a friend and arrested in Brussels, Belgium, where he was imprisoned for a year before he was tried for heresy and then was strangled and burned at the stake. His last words were, “Lord! Open the King of England’s eyes.” Within four years his prayer was answered when the King ordered four translations of the Bible to be published in English, all of which were based on Tyndale’s work.10

The Coverdale Bible

During the year Tyndale was imprisoned, two of his disciples completed translating the Old Testament into English. They were Myles Coverdale (c. 1488-1569) and John Rogers (c. 1500-1555). Although Tyndale has based his translation of the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Old Testament) on Hebrew texts, Coverdale and Rogers translated from Martin Luther’s German text (completed in 1534) and the Latin Vulgate.

Coverdale and Rogers took what they had done and combined it with Tyndale’s complete New Testament and his partial Old Testament translations to produce what came to be called the Coverdale Bible.11 It was published in 1535.

The Great Bible

Meanwhile, King Henry VIII had broken with Rome in 1534 over his divorce of Catherine of Aragon, and he was anxious to provide an official Bible for his new Anglican Church. Accordingly, the Archbishop of Canterbury hired Myles Coverdale for the task, and he produced in 1539 what came to be known as the Great Bible.12 Its name was based on its size since it measured over 14 inches in height.

This Bible was the first “authorized edition” to be published in England. The King ordered that it be distributed to every church and chained to each pulpit. He also ordered that a reader be provided so that the illiterate could hear the Word of God.13

The Matthew-Tyndale Bible

Coverdale’s collaborator on the Coverdale Bible, John Rogers, who operated under the pseudonym, Thomas Matthew, continued working on the Old Testament, determined to produce an English text based solely on Hebrew sources. He combined his work with the New Testament produced by Tyndale and published the Matthew-Tyndale Bible in 1549.

This was the first English language Bible to be based entirely on Hebrew and Greek texts.

Four years later, in 1553, the eldest daughter of King Henry VIII ascended the throne determined to restore England to Roman Catholicism. She was crowned Queen Mary I, and she immediately launched a severe religious persecution which ultimately resulted in almost 300 dissenters being burned at the stake, including John Rogers.14 “Bloody Mary’s” attack on the Reformers prompted a mass exodus to Europe.

The Geneva Bible

Many of those who fled Mary’s fury went to Geneva, Switzerland where John Calvin granted them asylum. There they began working on a new English translation. William Wittingham (c. 1524-1579) headed up the effort and oversaw the work of a skilled team of translators and biblical scholars which included Myles Coverdale.

In 1560 they produced the Geneva Bible which became one of the most historically significant translations of the Bible into English.15 It served as the primary Bible of the Protestant Reformation Movement and was the Bible used by William Shakespeare, Oliver Cromwell, John Milton, John Knox, John Donne, and John Bunyan. It was the first Bible to be brought to America, being transported across the ocean on the Mayflower.

The text of the Bible was not much different from the English versions that preceded it. In fact, more than 85% of the language came from Tyndale. What set it apart was its format and the study aids that were incorporated into it:

- It was the first English Bible with text that was divided into numbered verses.

- Extensive cross-referencing of verses was supplied.

- Each book was preceded with a summary introduction.

- Visual aids like maps, tables, and woodcut illustrations were added.

- It contained topical and name indexes.

- It featured an elaborate system of marginal notes designed to explain the meanings of verses.

Because of all these features, the Geneva Bible has often been referred to as the first study Bible. It was enormously popular, and it quickly replaced all other Bibles. Its popularity continued for decades after the King James Version was released in 1611.

The Bishop’s Bible

But the Geneva Bible was not popular among the rulers of England. Queen Mary had been succeeded by her sister, Elizabeth I, who returned England to the Protestant fold, but Elizabeth was a devout believer in the Divine Right of Kings, and the marginal notes of the Geneva Bible were strongly opposed to both monarchy and the institutional church. This led to the production in 1568 of a new authorized Bible called the Bishop’s Bible, which was a revision of the Great Bible of 1539. The Bishop’s Bible was never able to gain much acceptance among the people.16

The Douay-Rheims Bible

Meanwhile, the Roman Catholic Church had decided to give up its resistance to translations. Realizing they had lost the battle, they decided that if the Bible was going to be available in English, they might as well produce an official Catholic version.

They used the inaccurate Latin Vulgate as their source text, and in 1589 they published what was called the Douay-Rheims Bible.17 The New Testament was published in 1582. The Old Testament was completed over 30 years later in 1610. This version contained notes that were very polemical in nature, designed to counter the claims of the Protestant Reformation.

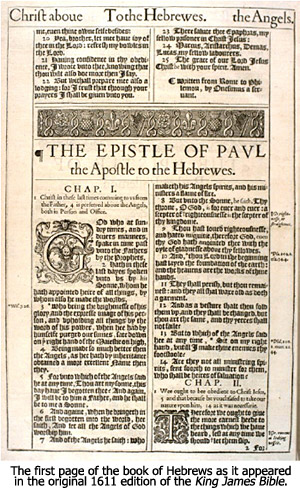

The King James Bible

Queen Elizabeth was succeeded in 1603 by Prince James VI of Scotland who became King James I of England. The King inherited a church that was deeply divided between the Conformists and the Puritans. To try to settle the differences, the King called a conference in January 1604. The conference failed to produce peace between the contending groups, but it produced a call for a new authorized version of the Bible.

The plea was accepted by King James. Like Elizabeth, he hated the Geneva Bible, but he recognized that the Bishop’s Bible was inferior. He desired to have a high quality English Bible that all his subjects could embrace.

A group of 47 translators were assembled, all from the Church of England. Detailed instructions were issued to guide the translation. Marginal notes were outlawed, except for the explanation of Hebrew or Greek words. The translation had to reflect the episcopal structure of the Church of England.18

The translators were authorized to consult other English translations, and they did so. In fact, their work turned out to be more of a revision of existing translations than it was an original translation. They acknowledged this fact in the preface they attached to the Bible:19

Truly (good Christian reader) we never thought from the beginning, that we should need to make a new Translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one… but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principal good one…

Again, like all the previous English versions, the King James Bible retained 85 percent of the New Testament text of Tyndale. And biblical expert Edgar J. Goodspeed contends that 19/20ths of the King James Version was borrowed from previous translations.20

In obedience to their instructions, the King James translators did not provide any marginal interpretations of the text. They did, however, provide 9,000 cross references and 8,500 notes regarding alternative renderings or variant source texts.

The Ascendancy of the King James Bible

The King James Bible did not become the predominant Bible overnight. Scholars stuck with the Latin Vulgate and abandoned it slowly over the course of the 18th Century. The general public clung to the Geneva Bible for decades.

The turning point for acceptance of the King James Version occurred after the death of King James in 1625. His successor, Charles I, appointed an Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, who immediately banned the printing of the Geneva Bible in order to bring about a uniformity of Bibles. At first, this caused no problem because copies could easily be imported. But Laud later issued a further edict forbidding the Bible’s importation. The last printing of this great Bible was done in Amsterdam in 1644.21

With no continuing competition, by 1700 the King James Version had become the sole English translation for use in the Protestant Churches.

Over the years that followed, the King James Version went through many revisions. Most of these were to correct spelling errors and typographical errors. By the mid-18th Century the misprints had reached scandalous proportions. It was then decided that an attempt should be made to produce a standard text.

The first attempt was by Cambridge University scholars in 1762. Another effort was made in 1769 by Oxford University, and that edition became the standard text that is still in use today.

The Oxford edition of 1769 differs from the 1611 text in 24,000 places. Spelling and punctuation were standardized. The “supplied” words not found in the original languages were greatly revised and extended as a result of cross-checking against the presumed source texts. And in many places minor changes to the text itself were made.22

The Decline of the King James Bible

The King James Bible remained supreme for a peak period of 250 years, from 1700 to 1950. During that time it became the only book in the world to exceed one billion copies.23

The first serious challenge to the King James Version appeared in 1885 when the English Revised Version was published in England. Its stated purpose was “to adapt the King James Version to the present state of the English language… and to the present standards of biblical scholarship.”24

The English Revised Version was noted for being the first Bible to ever be published without the Apocrypha (14 intertestament books). Until that time, all Bibles, both Protestant and Catholic — including the King James Bible — had been published with the Apocrypha.

American scholars followed suit in 1901 with the publication of the American Standard Version. It was nearly identical to the English Revised Version except for the much more frequent use of the term Jehovah in the Old Testament.25

By the mid-20th Century the wording of the King James Version had become antiquated to the point that many words were unintelligible and others actually meant the opposite of their original meaning. This serious problem prompted an explosion of new translations and paraphrases during the second half of the century.

Recent American Translations

The Revised Standard Version of the New Testament appeared in 1946. The Old Testament text came out in 1952.26 This version was denounced by conservatives as a “liberal translation.” Particularly controversial was its translation of Isaiah 7:14 where the word previously translated as “virgin” was changed to “young woman.” This Bible was quickly adopted by most of the mainline denominations.

In 1971 the complete New American Standard Bible was published.27 It constituted an extensive revision of the American Standard Bible of 1901. It was quickly adopted by Evangelicals because it is considered by many to be the most accurate word-for-word translation that has been produced in the English language. It was updated in 1995 to make it more readable.

The New International Version was published in full in 1973.28 It offered a “dynamic equivalent” conservative translation, meaning it sought thought-for-thought accuracy rather than word-for-word. It was also aimed at a junior high school reading level. It was ridiculed by Fundamentalists as the “Nearly Inspired Version,” but it has quickly become the best-selling modern-English translation.

The New King James Version appeared in 1982.29 It attempted to keep the basic wording of the old King James Version in order to appeal to King James loyalists. It replaced most of the obscure words and the Elizabethan “thee, thy, and thou” pronouns. There was also an attempt to update grammar, spelling, and word order.

The dawn of the 21st Century saw the publication of the English Standard Version in 2002.30 It represents a major attempt to bridge the gap between simple readability and the precise accuracy of the New American Standard Bible. And like the old Geneva Bible, the English Standard Version has been issued in the form of a phenomenal Study Bible (2008) that is full of charts, maps, diagrams, and explanations that run 2,750 pages in length!

The Response of King James Defenders

As you can see, there has been a flood of new translations since 1950, and the listing above does not contain paraphrases that range from the conservative (The Living Bible) to the liberal (The Message). Nor have I listed a number of very liberal translations. When you consider the sudden appearance of all these translations, there can be no doubt that people are seeking Bibles they can easily understand.

All these new Bibles have promoted King James users to dig in their heels. They greet every new version with derision and harsh criticism. Often their attacks get out of hand as they dub the new versions “Satan inspired.” Some even argue that the King James Version is a sacred, inerrant translation and that it is therefore the only “perfect” translation that exists today.31 Any survey of the history of English Bibles like the one I have presented above makes the King James perfection claim a laugh.

The more responsible critics usually point to what they call the “erosion” of the New Testament by the modern translations. They argue that the Greek text for the New Testament that was compiled by Erasmus (1466-1536) and published in 1516 is the only proper basis for a New Testament translation, and they point out that it was what was used for the King James Version. This text became known as the Textus Receptus.

They then attack the modern translations for abandoning the Textus Receptus and relying instead on the Greek text compiled by B. F. Westcott and F. J. A. Hort and published in 1881. They argue that although the Westcott and Hort version is based upon much earlier manuscripts than those used by Erasmus, the manuscripts are unreliable because they are “Catholic manuscripts.” This accusation is based on the fact that one of the manuscripts was found at a Catholic monastery in the Sinai desert and the other at the Vatican in Rome.

These attacks on the Westcott-Hort text are really irrelevant, for although the Westcott-Hort text was the “standard” critical Greek text for a couple of generations, it is no longer considered as such, and it has not served as the New Testament text for any of the modern translations. The standard text today is the Nestle-Aland text (1st edition in 1898; 27th edition, 1993).

The truth of the matter is that none of the Greek texts are perfect. They represent a pasting together of segments of the most ancient manuscripts. Erasmus did his best, but there have been thousands of manuscripts discovered since he put together his compilation, and many of those are much older than anything he had to work with. Furthermore, none of the differences in the compilations have any effect on the basic doctrines and truths of the New Testament.

The King James defenders need to keep in mind that the major purpose of the new conservative translations is twofold: greater accuracy and easier to understand language. How can you fault those aims? Here’s how one person has summed it up:32

We must remember that the main purpose of the Protestant Reformation was to get the Bible out of the chains of being trapped in an ancient language that few could understand, and into the modern, spoken, conversational language of the present day. William Tyndale fought and died for the right to print the Bible in the common, spoken, modern English tongue of his day…

Will we now go backwards and seek to imprison God’s Word once again exclusively in ancient translations?

Thanks to the King James Version

The King James Version was a great Bible for its day and time. It has served the English speaking peoples well for several centuries. The time has come to lay it to rest with honor and dignity and with heart-felt thanks. It has stamped our language indelibly. It has inspired many generations. Most important, it has opened the door to God for millions of people by delivering them from spiritual darkness into the light of the glory of Jesus Christ.

Notes

1) Wikipedia, “Vulgate,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vulgate.

2) Wikipedia, “Jerome,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerome.

3) Wikipedia, “Septuagint,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Septuagint.

4) Wikipedia, “John Wycliffe,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Wycliffe.

5) John L. Jeffcoat III, “English Bible History,” www.greatsite.com/timeline-english-bible-history, page 10.

6) Wikipedia, “John Wycliffe,” page 13.

7) Jeffcoat, “English Bible History,” pages 1-2.

8) Wikipedia, “Johannes Gutenberg,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johannes_Gutenberg.

9) Wikipedia, “William Tyndale,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Tyndale.

10) Ibid., page 4.

11) Widipedia, “Coverdale Bible,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coverdale_Bible.

12) Wikipedia, “Great Bible,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Bible.

13) Jeffcoat, “English Bible History,” page 4.

14) Wikipedia, “Mary I of England,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_I_of_England.

15) Wikipedia, “Geneva Bible,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geneva_Bible.

16) Jeffcoat, “English Bible History,” page 6.

17) Wikipedia, “Douay-Rheims Bible,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douay%E2%80%93Rheims_Bible.

18) For a list of all the instructions given by King James to the translators, see, “History of the King James Version,” www.bibleresearcher.com/kjvhist.html, pages 2-3.

19) Edgar J. Goodspeed, “The Translators to the Reader: Preface of the King James Version of 1611,” http://watch.pair.com/thesispreface.html, page 5.

20) Ibid., page 4.

21) Dr. Herbert Samworth, “The King James Bible,” http://www.solagroup.org/articles/historyofthebible/hotb_0015.html, page 3.

22) Wikipedia, “Authorized King James Version,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Authorized_King_James_Version, page 20.

23) Jeffcoat, “English Bible History,” page 7.

24) Wikipedia, “Revised Version,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revised_Version, page 1.

25) Ibid., page 2.

26) Wikipedia, “Revised Standard Version,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revised_Standard_version.

27) Wikipedia, “New American Standard Bible,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_American_Standard_Version.

28) Wikipedia, “New International Version,” http://en.wikipedia/wiki/New_International_Version.

29) Wikipedia, “New King James Version,” http://en.wikipedia/wiki/New_King_James_Version.

30) Jeffcoat, “English Bible History,” page 9.

31) For an example of a “KJV Only” article, see: James L. Melton, “How I Know the King James Bible is the Word of God,” www.avi611.org/kjv/knowkjv.html.

32) Jeffcoat, “English Bible History,” page 9.