The Revival of the Hebrew Language

Israel in Bible Prophecy

For many years I have been taking pilgrimage groups to the Holy Land. One of the places we always visit is the Dead Sea Scrolls Museum in Jerusalem. The centerpiece of the museum is the Isaiah scroll that is displayed in a circular glass case.

I usually gather my group around the scroll, explain its importance and then turn the group loose to explore the rest of the museum. One year, after releasing the group, as I was walking away from the Isaiah scroll, I heard someone behind me suddenly start speaking loudly in Hebrew. When I turned around to see who it was, I discovered a young boy about 13 years old with his parents. The boy was reading the scroll, using a pointer. I supposed he was practicing for his Bar Mitzvah, for reading a section from the Scriptures is always a part of that ceremony.

As I listened to the young man, I realized I was witnessing a miracle. It occurred to me that a Greek boy of his age could not read the Greek writings of Homer (ca 8th Century BC) nor could an American or British boy read the English of Chaucer (14th Century AD). Yet this boy could read Hebrew written 2,000 years ago.

How was that possible? Because biblical Hebrew has been revived from the dead and is spoken as the national language of Israel today.

The Death of the Hebrew Language

But I am getting ahead of my story. Let’s return for a moment to the days of the Bible.

The worldwide dispersion of the Jewish people began in 70 AD when the Romans ruthlessly ended their revolt against Roman rule by destroying the city of Jerusalem, including their marvelous Temple. This dispersion from their homeland was accelerated after their second revolt was put down in 136 AD.

As the Jews were scattered, they gradually stopped speaking their native language during the centuries that followed. Those in Europe took German and mixed it with Hebrew, producing a hybrid tongue called Yiddish. The Jews who settled in the Mediterranean basin mixed Hebrew with Spanish and developed a language called Ladino.

Hebrew became confined to the synagogues where it was used for Torah readings. By the beginning of the 20th Century, most Jews could not understand the Torah readings. For them, it was like a Gentile experiencing a Catholic mass conducted in Latin.

But all this was to change miraculously, and in the process, the fulfillment of a very important end time Bible prophecy began.

The Key Prophecy

The prophecy I have in mind is one about the revival of the Hebrew language. It is found in Zephaniah 3:9 —

For then I will restore to the peoples a pure language, that they all may call on the name of the LORD, to serve Him with one accord. (NASB)

The New International Version states that the Lord will “purify the lips of the people.” The New Living Translation says God will “purify the speech.” The English Standard Version puts it this way: “I will change the speech of the peoples to a pure speech.” The Living Bible paraphrases the verse to read: “At that time I will change the speech of my returning people to pure Hebrew so that all can worship the Lord together.”

The more literal translations of this verse leave the clear implication that the ultimate fulfillment of this prophecy will occur when all the peoples of the world are once again unified in their language, likely speaking biblical Hebrew. Whether this will occur during the Millennium or the Eternal State is not made precisely clear in the Scriptures.

For example, Isaiah 19:18 says that during the Lord’s millennial reign, there will be cities in Egypt where people will be speaking Hebrew. And our key verse, Zephaniah 3:9, is set in the context of being fulfilled after God has poured out His “indignation” on the nations (Zephaniah 3:8). That’s speaking of the Tribulation, so the implication is that the establishment of a universal language will occur at the beginning of the Millennium.

On the other hand, Zechariah 8:23 tells us that during the Millennium, “ten people from all languages and nations will take hold of one Jew by the hem of his robe and say, ‘Let us go with you, because we have heard that God is with you'” (NIV). So, it sounds like national languages will continue during the Millennium, and thus the unity of language will not occur until we reach the Eternal State.

But, as you will see, the revival of biblical Hebrew as the spoken language of the Jewish people today must be considered a miracle of God and at least a partial fulfillment of Zephaniah 3:9. In that regard, it should be noted that there is no other example in world history of an ancient language being revived as the spoken language of a modern nation. The restoration of biblical Hebrew to a modern day spoken language is a unique historical phenomenon.

The Key Person

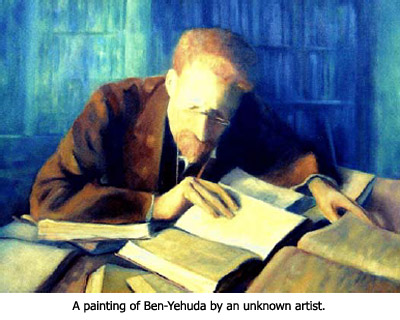

God orchestrated the revival of spoken Hebrew through a baby born to an Orthodox Jewish family in 1858 in Lithuania, which at that time was part of Russia. He was given the name of Eliezer Yitzhak Perlman.

When Eliezer was 5 years old, his father died of tuberculosis. A few years later, the boy was sent to live with his mother’s wealthy uncle, who was a stern taskmaster. As soon as Eliezer turned 13 and celebrated his Bar Mitzvah, he was sent to a yeshiva (Rabbinical training school) in Belarus. There he fell under the influence of a young progressive rabbi who was caught up in the Jewish Enlightenment Movement.

The Key Teacher

One day the rabbi asked Eliezer to stay after class. When all the other students had left, the rabbi handed Eliezer a book and ask him to read it aloud. It was a Hebrew translation of Robinson Crusoe, and Eliezer was amazed by it.1 This was in 1872.

Eliezer’s amazement was rooted in the fact that Orthodox Jews considered the Hebrew language to be a holy language that was appropriate only for use in the synagogue and for Rabbinical writing.2 To use it for secular purposes was considered ungodly and blasphemous.3 In fact it was taken to be an attack on the Jewish religion.4

From the moment Eliezer saw that Hebrew could be used for other than liturgical purposes, he was hooked on it and its revival as a spoken language. Near the end of his life, while thinking back on that moment, he wrote: “Since the first glance at a Hebrew Robinson Crusoe, I fell in love with the Hebrew tongue as a living language. This love was a great and all-consuming fire that the torrent of life could not extinguish.”5

The Key Situation

Eliezer had grown up with Yiddish as his natural spoken language. He was a prodigy, so at the age of 3 he was reading Hebrew in the Scriptures and prayer books. But it was not used for everyday conversation, and not only because it was considered holy. Another problem was the fact that it did not contain sufficient words to carry on a modern day conversation.

It is estimated that in the 1880s only about 50 percent of all male Jews could understand the Hebrew readings in the synagogue, and as few as 20 percent could read a book written in Hebrew.6 In that same decade, the Jewish poet, Yehuda Leib Gordon (1830-1892), wrote: “Perhaps I am the last of Zion’s poets, and you are the last readers.”7 Although Gordon was a part of the Jewish Enlightenment, he saw little hope for Hebrew becoming a daily spoken language or even a language of literature.

Hebrew, because of its lack of use, was just too clumsy. One of Eliezer’s biographers summed it up this way:8

Young writers preferred to write in Yiddish or in a European language, full of feeling and color. By contrast, Hebrew was bare and stiff, the dry language of the scholar. No one used Hebrew for everyday expressions. Orthodox Jews had a different reason for not speaking Hebrew. They believed it was wrong to use a holy language to say something like, “Take out the garbage.”

Moshe Lilienblum (1843-1910), who was considered the “dean” of Hebrew authors at the time Eliezer was introduced to Robinson Crusoe in Hebrew, was also disillusioned with the future of the language. In a newspaper article, he announced that “Hebrew’s time has passed, and it no longer has a purpose or task in Jewish life.”9

The Key Family

When Eliezer’s great-uncle discovered that the boy had fallen under the influence of a teacher mixed-up in the Jewish Enlightenment, he pulled him out of the yeshiva and disowned him. Eliezer wandered about on his own and ended up at a synagogue in Russia. There he met a remarkable man named Solomon Jonas who asked the boy to come live with his family. Jonas was a wealthy whiskey maker with six children of his own, the oldest of which was a daughter named Deborah who was 18 years old.10

Eliezer lived with this family for the next two years and was tutored by Deborah in French, German and Russian. During that time, his heart grew fond of Deborah.11

At the age of 16, Eliezer’s adopted father decided he needed to pursue his education at a state school in Latvia. But this, as we will see, was not the end of Eliezer’s relationship with the Jonas family.

It is significant to note that during his stay with the Jonas family, Eliezer developed a constant cough.12

The Key Event

Eliezer’s time at the state school was to prove to be a pivotal period in his life. During that time he was introduced to the concept of nationalism, and he became a zealot in behalf of it.13

In 1877 Russia went to war against the Ottoman Empire in behalf of the liberation of the Balkans. And the concept of nationalism — “one state for each nation” — became the battle cry that swept Europe and which ultimately led to the outbreak of World War I.

The war in the Balkans captured Eliezer’s imagination and awakened within him the idea that the Jewish nation, like all other nations, deserved its own state. Here’s how he explained it:13

After a number of hours of reading the papers and reflecting on the fate of the Bulgarians and their future freedom, suddenly, as if lightning struck, an incandescent light radiated before my eyes… and I heard a strange inner voice calling to me: “The revival of Israel and its language in the land of the forefathers!”… The lot was cast. My life and strength were given from that time onto the labor of reviving Israel and its tongue in the land of the fathers.

The Key Diagnosis

In 1878, at the age of 20, Eliezer arrived in Paris where he intended to study medicine. But his heart was in Palestine, as his homeland was called at that time. And his zeal was for the revival of the Hebrew language as a spoken tongue.

But all his dreams and hopes were suddenly derailed by his nagging cough. He finally went to a doctor for a diagnosis, and the news he received was devastating. He had developed tuberculosis.

He immediately wrote to Deborah to inform her. “I have the feeling of a person condemned to death,” he wrote. He continued, “For this reason I work now without sleep to put onto paper the reaons why it is so important for the Jewish world to become inflamed with the idea of returning to the land of our forefathers…”14 He then focused in on his greatest concern:15

I have decided that in order to have our own land and political life, it is also necessary that we have a language to hold us together. That language is Hebrew, but not the Hebrew of the rabbis and scholars. We must have a Hebrew language in which we can conduct the business of life. It will not be easy to revive a language dead for so long a time.

Eliezer closed this letter with a statement that would become his lifelong motto: “The day is short; the work to be done is so great!”

In his next letter to Deborah, he signed it Ben-Yehuda, and he added this postscript: “Do not be surprised that I sign a new name to my letter. This is the name which will appear over my articles. Someday I shall find the way to make it my own.”16

His new name had a double meaning. His father’s given name had been Leib, which was Yiddish for Yehuda. Thus, Ben-Yehuda meant Son of Yehuda. But Yehuda is the Hebrew word for Judea, and so the new name also meant that he considered himself to be a Son of Judea — a son of the land of his forefathers.17

The Key Articles

In 1879, when Ben-Yehuda was only 21, a prestigious Vienna newspaper published an article of his titled, “A Burning Question.” The editor changed the name to “A Weighty Question.” It was to be one of the first ever Zionist manifestos, calling on the Jewish people to return to their homeland.

In the article, Ben-Yehuda became the first person to call for the revival of Hebrew as an everyday language.18 In the process of writing the essay, Ben-Yehuda had to invent a new Hebrew word for nationalism: leumiut.19 He signed the article with his new name — Eliezer Ben-Yehuda.

Predictably, the Orthodox Jews reacted furiously, denouncing Ben-Yehuda as a pagan because he had the audacity to suggest that their holy language be defiled by using it for everyday conversation.20 But Ben-Yehuda was not deterred. He immediately responded to his critics with a second article which he titled, “And We Have Still Not Learned Our Lesson.”21

In it he decried the political and philosophical divisions among the Jewish people and called for unity. He wrote, “Why do we not see, all of us whose eyes are so keen, that if we do not hurry to unite, the end is near, the horrible end of the hope of our people for an eventual redemption?” He then proceeded to ask a rhetorical question: “What is this one point on which all of us can unite?” His obvious answer: “The resettlement of the Land of Israel.”22

A Key Discovery

In 1880 Ben-Yehuda decided to take the advice of his doctor and go to Algiers in North Africa where he was assured the climate would be much better for his health. The advice proved true.

But what turned out to be more significant was a linguistic discovery Ben-Yehuda made there. For the first time, he encountered Hebrew as spoken by Sephardic Jews — the Jews who had settled around the rim of the Mediterranean Sea. He discovered that their pronunciation of Hebrew was so different from his Ashkenazic pronunciation that he could not understand them, nor could they understand him.23

As he studied their system of pronunciation, he fell in love with it. He found it to be more flowing and melodic, more natural to the lips and easier on the ears.24 Deciding rather arbitrarily, Ben-Yehuda concluded that the Sephardic pronunciation had to be closer to the original in biblical times, and he demanded it and taught it from that day forward.25

The Key Land

Although the climate of North Africa was very beneficial to Ben-Yehuda’s health, he decided that if he was destined to die from TB, he would die in his homeland. So he decided to move to Palestine and reside in Jerusalem.

This was an incredible decision for anyone in that day and time, especially for a sick person. Palestine was a barren wasteland full of great hardships, and Jerusalem was an incubator of diseases — a backwater town where the sewage ran down the middle of the streets.

Before departing, Ben-Yehuda felt compelled to write Solomon Jonas and let him know he had decided not to marry Deborah because any wife of his would face terrible hardships and diseases and the possibility that he might die at any moment.26 But despite this letter and the fact they had not seen each other in seven years, Deborah would have none of it. She wrote back and insisted they get married. She stated that she was as bound to his fate as Ruth of biblical times had been bound to the fate of her mother-in-law, Naomi.27

They were married in Cairo in 1881. She was 27; he was 23. They agreed that Deborah’s name would be changed to the Hebrew equivalent of D’vorah.28 They also agreed that they would never again speak to each other in any language except Hebrew — despite the fact that D’vorah spoke little Hebrew and the language lacked words for many everyday things.29 This led to communication through a lot of hand signals and finger pointing over the next few years.30

The couple proceeded immediately to Palestine and arrived at the port of Jaffa in the fall of 1881. From there they traveled by carriage to Jerusalem where they resided for the next 41 years. Many years later, Ben-Yehuda wrote that he had only two regrets in life: “There are two things for which I am sorry, and for which I can find no consolation: I was not born in Jerusalem, or even in the Land of Israel, and the first words I spoke were not spoken in Hebrew.”31

The Key City

For 2,000 years, ever since their expulsion from the land by the Romans, the Jews in the Diaspora had been ending their prayers with the phrase, “Next year in Jerusalem.” At long last that prayer had been answered for Eliezer and D’vorah. But the Jerusalem they found was not the Jerusalem of Scripture which is referred to in Isaiah as “a crown of beauty in the hand of the Lord” (62:3) and “a praise in the earth” (62:7).

Instead, the city proved to be what they had been warned it would be. They found a small town of only 25,000 residents who were living in filth.32 The Jews constituted about half the population, but they were divided up into close-knit communities that had little to do with each other. And to Ben-Yehuda’s despair, he discovered them speaking Ladino, Yiddish, Arabic, Spanish and Russian — but no Hebrew.33

At first, they tried to court the Orthodox community by dressing like Sephardic Jews, observing the kosher laws and attending the synagogue services on the Sabbath.34 But this effort proved to be of no avail. Ben-Yehuda’s reputation as a Zionist with the aim of reviving Hebrew as a spoken language had preceded him. The result was that the Orthodox community, especially the Ashkenazis (European Jews), ostracized them.

Ultimately, this treatment convinced Ben-Yehuda and his wife that they should return to European ways and dress. Accordingly, Ben-Yehuda cut off his side curls, shaved his long beard into a closecut goatee and started wearing suits instead of robes.35 This change convinced the Orthodox that they had been right all along in viewing the couple as pagans.

Ben-Yehuda’s zeal became focused. He made a large sign of his motto (“The day is short; the work to be done is so great!”), and he hung it on the wall above his stand-up desk (he argued that he could think better standing up).36 He proceeded to work 15 to 19 hours each day, most of it standing!

The Key Plan

Ben-Yehuda had a very specific plan in mind when he arrived in Jerusalem, and he pursued it fanatically and methodically. It consisted of several elements:37

- Encourage the speaking of Hebrew in each home.

- Establish a newspaper and work through it to report the news in Hebrew, creating new words as needed.

- Do everything possible to introduce the teaching and speaking of Hebrew into the schools.

- Produce a dictionary of the Hebrew language to aid in its daily utilization.

Hebrew in the Home

Ben-Yehuda began the implementation of his plan by starting with his own home. He laid down the rule that no language could be spoken within his house except Hebrew. He wanted his family to be a model for others. And thus, when D’vorah became pregnant, he announced that the baby she was carrying would become the first true Hebrew child in 2,000 years because it would be allowed to hear only biblical Hebrew.38 That meant no playmates, and it meant almost total isolation at home.

Their friends were aghast over such fanaticism. They pleaded with Ben-Yehuda to change his mind, arguing that the child would grow up either as a mute or an idiot.39 But Ben-Yehuda would not budge.

In 1882 D’vorah gave birth to this first child, a boy who was named Ben-Zion Ben-Yehuda, meaning Son of Zion and Son of Judea.40 And just as Ben-Yehuda had promised, the son was kept isolated from the world so that he would not become “contaminated” by hearing any foreign language.

Friends and neighbors continued to protest the boy’s isolation. And their harassment became even more passionate when four years passed without Ben-Zion speaking a word. All he did was babble. But shortly after his fourth birthday, he spoke his first word — Abba, meaning “Father.”41 From that point on he spewed forth a torrent of words and, like his father, he began to make up new words for items around the house!42

The Hebrew Newspaper

Ben-Yehuda launched the publication of a newspaper shortly after his arrival in Jerusalem, not only because it was part of his master plan, but also because he needed the income to survive. The general population in Jerusalem liked the paper. They had never seen anything like it in the Hebrew language. The settlers in the agricultural villages scattered across Palestine loved it. But the Orthodox were determined to destroy it and tried to do so on several occasions.

To publish the paper, Ben-Yehuda had to constantly create new words. His first challenge was to come up with a word for “newspaper.” The word used in Jerusalem was michtav-et, which literally meant, “a letter of the time.” Ben-Yehuda considered this term to be clumsy, so he took the Hebrew word for “time” and, improvising a bit, he came up with the new word, itton, which received public acceptance.43

Other words for which he had to manufacture new Hebrew words were soldier, airplane, sport, doll, ice-cream, jelly, omelette, handkerchief, towel, bicycle — and hundreds more.44

Sometimes his new words were rejected. One such word was the one he introduced for “tomato.” The commonly used word already in circulation was agbanit, taken from a root word that meant “to love sensuously.” Ben-Yehuda thought that was inappropriate, so he coined the word, badurah. The Hebrew speakers stuck with agbanit.45

Ben-Yehuda was a purist. He would never just transfer a word like “telegraph” into the Hebrew language via a transliteration. No, the new word had to be based on a root Hebrew word.46

The Opposition

Opposition to Ben-Yehuda’s efforts never let up during his lifetime. The Orthodox were unrelenting in their efforts to prevent their holy language from becoming a secular tongue.47

At one point, the Ashkenazic leadership went to the Ottoman rulers and accused Ben-Yehuda of treason, based upon a passage in his newspaper which they had purposefully mistranslated. This resulted in his arrest, trial and conviction. And although he was released on bail, pending an appeal, he was prohibited from publishing his newspaper. He was delivered from this ordeal by Baron Edmond de Rothschild (1845-1934), a French philanthropist and supporter of Zionism, who paid bribes to the prosecutors and judges.48 During this legal crisis, Ben-Yehuda and his family were formally excommunicated by the Ashkenazic leaders.49

Opposition from secular Jews was not so passionate, but it was also persistent. It came mainly in the form of a lack of interest. After all, most of the Jews who formed the nucleus of the Zionist Movement in the 1890s and early 20th Century were Humanists, Socialists, or Communists, and most were Atheists or Agnostics. They had no interest in speaking a biblical language.

Theodor Herzl (1860-1904), considered to be the father of Zionism, is a good example. He was a thoroughly secular person. He considered Hebrew to be “unfeasible,” and preferred German instead.50 Other Zionists advocated Yiddish.

Ben Yehuda was a great admirer of Herzl and traveled to meet him personally several times, but he could never seem to catch up with him. He finally was able to meet Herzl in 1898 when he came to Palestine to confer with Kaiser Wilhelm II during the German leader’s visit to the Holy Land. Herzl showed a complete lack of interest in Ben-Yehuda’s ideas. That evening, Herzl wrote in his diary:51

I also met a young fanatic who tried to convince me that what our movement needs is to adopt Hebrew as our national language. It is, of course, ridiculous!

The Two Faithful Wives

Throughout all the stress and strain of living in a harsh environment while battling a deadly disease and fighting constant battles to achieve what seemed to be an impossible task, Ben-Yehuda was supported and constantly encouraged by two remarkable wives.

The first was D’vorah who bore him five children while helping him edit his newspaper. She suffered quietly as she was scorned by neighbors and rarely had enough money to put food on the table. Ben-Yehuda always referred to her as “the first Hebrew mother in two thousand years” because she was the first to give birth to children who grew up speaking Hebrew as their native language.52

D’vorah contracted her husband’s tuberculosis and died rather suddenly in 1891 at the age of 37. Ben-Yehuda’s words of honor for her, which he published a week later in his newspaper, consisted simply of a quote from Jeremiah 2:2 — “I remember you, the kindness of your youth, the love of your espousals, when you went after me in the wilderness, in a land that was not sown.”53

Ben-Yehuda’s grief was compounded two months later when his three youngest children died during a flu epidemic.54 He was 33 years old, and he desperately needed consolation and help.

Once again, the help came from the Jonas family. Shortly before her death, D’vorah had written to her younger sister, Paula, asking her to take her place as Ben-Yehuda’s wife.55 Solomon Jonas and his wife were appalled by the request since they considered it to be a death warrant for another daughter. But like her older sister, Paula could not be deterred. She had always loved Ben-Yehuda, and she considered it her destiny to take her sister’s place and assist him in the accomplishment of his monumental task. She was only 19 years old, so her entire family decided to go with her and make Aliya!56

Paula wrote to Ben-Yehuda with the news and requested that he send her a list of possible Hebrew names for herself. Like her sister, she desired to change her name. Ben-Yehuda sent the list and she picked the name of Hemda, not because she liked the way it sounded, but because of its meaning: “beloved or cherished.”57

Hemda proved to be every bit as faithful, resourceful, supportive and helpful as D’vorah had been. During her 30 years with Ben-Yehuda (1892-1922). She bore him 6 children. She toured all of Europe several times raising financial support for his research and writings. And she was the one who found a prestigious German publisher for his dictionary.

The Hebrew Dictionary

One of Ben-Yehuda’s greatest achievements was his creation of a dictionary of the Hebrew language. He began the project by creating a new word for “dictionary.” The expression people had been using was sefer millim, which meant “book of words.” He shortened this to one word, millon.58

Ben-Yehuda spent most of his life searching for ancient Hebrew words that had been lost. He also sought to find the origin of words and examples of their usage, as well as their changes in meaning throughout the centuries. He scoured libraries all over Europe and the Middle East. And when he moved to the United States during World War I to escape Turkish persecution, he spent 4 years searching the great libraries of this nation which were located in the Northeast.59

When he fled Palestine in 1914, he had already accumulated about 450,000 notes. He packed them up and turned them over to the American consulate in Jerusalem for safe-keeping.60 Those notes were taken from over 40,000 books he had consulted that had been written over a period of more than two thousand years.61

What he sought to produce was much more that what we think of as a dictionary. His goal was no less than an encyclopedia of the Hebrew language. He provided definitions of each word in Hebrew, French, German and English. He identified the origin of each word and provided its sister words in other Semitic languages. He provided synonyms and antonyms. He traced the changes in the meaning of the word through the centuries. And he provided overwhelming examples of the use of the word in sentences to help the reader see how to use the word in conversations.62 For example, the dictionary provided 335 expressions for the word lo, which means “no,” and 210 for ken, which means “yes.”63 The first volume, published in 1908, covered only the letters aleph and beth.64 There are 22 letters in the Hebrew alphabet, of which five have different forms when used at the end of a word.

Ben-Yehuda’s Triumph

By 1917, Ben-Yehuda had made such progress on his dictionary and with his effort to resurrect spoken Hebrew from the dead, that he changed the motto on his wall to read: “My day is long; my work is blessed.”65

Later that year, a dream of his came true. The British issued the Balfour Declaration in November, proclaiming their intention after the war to make Palestine a home for the Jewish people. The next month the city of Jerusalem fell to the Allied Forces, liberating the city from 400 years of Turkish rule.

Ben-Yehuda responded to these momentous events with a paraphrase of Psalm 126: “T’was like a dream when the Lord restored Zion from its bondage.”66

His greatest victory came in 1921 when the British government recognized three official languages for Palestine: English, Arabic and Hebrew. Postage stamps were issued in Hebrew for the first time ever, anywhere in the world.

By 1922 five volumes of his dictionary had been published, and he had finished writing volumes 6 and 7. His work had received worldwide acclaim.

On December 14, 1922 he finished working on the word nefesh,” meaning “soul” or “spirit.” The next day was Friday, Sabbath eve and the second day of Hanukkah. He told his wife that the next word he would be working on meant “take a breath,” and he took that as a word from the Lord that he should take the day off and rest over the Sabbath.67

He spent the day walking around his beloved city of Jerusalem. When he returned home, he turned pale and his breathing became labored. He laid down on a sofa to rest, and his wife sent word for doctors. Before long the word had spread all over Jerusalem that he was seriously ill, and the house quickly filled with doctors, city officials and friends.

Ben-Yehuda seemed to have drifted into a coma, but he suddenly raised up on an elbow, looked around the room and said, “Speak Hebrew!” Later, he called for his wife. She asked him if he felt better. His reply was, “Hebrew makes me rest.”68 Those were his last words. He was 64 years old.

Hebrew Today

Ben-Yehuda’s wife, Hemda, and her son, Ehud, worked together with linguistic experts to complete the dictionary. It ran a total of 17 volumes and was not completed until 1958, seven years after her death in 1951 at the age of 78.69

In the process of compiling his dictionary, Ben-Yehuda had realized there was a need for a group of linguistic experts to help him form new words and to serve as a monitor for the usage of the language. Also, there would be a need to keep his dictionary updated. He therefore formed a group in 1890 which he called The Hebrew Language Committee.70 It continues to operate to this day as the Academy of the Hebrew Language of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. It averages the creation of 2,000 new Hebrew words each year.71

Also during his lifetime, Ben-Yehuda had developed an intensive method of teaching Hebrew in which only Hebrew was used. It was so effective that his second wife became proficient in the language in only six months.72 That method is still used today in what are called “ulpan schools.” There are approximately 220 of these schools in Israel today teaching over 25,000 students, most of them new immigrants.73

There are nearly 200 book publishers in Israel today, and each of them is releasing between 5 and 150 new Hebrew language books per year.74 An Israeli writer, S. Y. Agnon (1887-1970) was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in 1966 for his Hebrew language novels.75 As of 2013, there were about 9 million Hebrew speakers worldwide, of whom 7 million spoke it fluently.76

Conclusion

Ben-Yehuda’s grave is situated on the lower slope of the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem. The words on his tombstone read:77

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, reviver of the Hebrew tongue and composer of the great dictionary. Dead in Jerusalem on the 26th day of Kislev in the sixth year of the Balfour Declaration.

Looking back on his life, the greatest miracle may not have been his revival of Hebrew as a spoken language. Rather, it may well have been God’s preservation of his life for 41 years after he was told he had only six months to live.

What is without doubt is that his accomplishment is proof positive that the Bible is the Word of God, that God is in control of history, and that we are living in the season of the Messiah’s return.

Notes

In addition to numerous articles on the Internet, this article is based primarily on three books:

1) Ben-Yehuda, Eliezer, Fulfillment of Prophecy: The Life of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda 1858-1922 (Privately printed, 2008), 377 pages. The author of this book is Ben-Yehuda’s grandson who has the same name as his grandfather. Based on letters, family remembrances and unpublished autobiographical segments written by Ben-Yehuda about his early life.

2) Drucker, Malka, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda: The Father of Modern Hebrew (New York: Lodestar Books, 1987), 81 pages. A brief but very insightful biography. Particularly valuable with regard to insights about the Hebrew language.

3) St. John, Robert, The Life Story of Ben-Yehuda: Tongue of the Prophets (Noble, OK: Balfour Books, 2013), 393 pages. This book was originally published in 1952. Based on conversations with Ben-Yehuda’s second wife, Hemda, and a biography she wrote about her husband in Hebrew. Also, based on interviews with friends and scholars who knew him personally.

Since the beginning of this ministry in 1980, we have stocked and sold copies of Robert St. John’s outstanding biography. It has recently been re-published by Balfour Books in a beautiful new edition, with a foreword by Israel expert Jim Fletcher.

References

1) Robert St. John, The Life Story of Ben-Yehuda: Tongue of the Prophets (Noble, OK: Balfour Books, 2013), pages 23-26. This book was originally published in 1952. It is based on conversations with Ben-Yehuda’s second wife, Hemda, and a biography she wrote about her husband in Hebrew. It is also based on interviews with friends and scholars who knew Ben-Yehuda personally.

2) Libby Kantorwitz, “Eliezer Ben-Yehuda and the Resurgence of the Hebrew Language,” The Jewish Magazine, www. jewishmag.com.

3) Malka Drucker, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda: The Father of Modern Hebrew (New York: Lodestar Books, 1987), page 6. A brief but very insightful biography, particularly regarding the nature, use and development of the Hebrew language.

4) Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, Fulfillment of Prophecy: the Life Story of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda 1858-1922 (Privately printed, 2008), page 115. The author is Ben-Yehuda’s grandson who has the same name as his grandfather. Based on letters, family remembrances and unpublished autobiographical segments written by Ben-Yehuda about his early life.

5) Ben-Yehuda, page 16.

6) Jack Fellman, “Hebrew: Eliezer Ben-Yehuda & the Revival of Hebrew,” www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org, page 5.

7) Barry Rubin, Assimilation and its Discontents (New York: Times Books, 1995), page 4.

8) Drucker, page 17.

9) Ben-Yehuda, page 26.

10) St. John, pages 29-35.

11) Ben-Yehuda, pages 19-23.

12) St. John, page 35.

13) Ben-Yehuda, page 28.

14) St. John, page 43.

15) Ibid.

16) St. John, page 44.

17) Ibid., 46.

18) Ben-Yehuda, pages 48-50.

19) Drucker, page 20.

20) Ibid., page 21.

21) Ben-Yehuda, page 51.

22) Ibid.

23) Drucker, page 22.

24) Ben-Yehuda, pages 55-56.

25) Ibid., page 57.

26) Ibid., pages 62-63.

27) Ibid., pages 68-72.

28) Drucker, page 24.

29) Ibid., page 23.

30) Ibid., page 29.

31) Ben-Yehuda, page 82.

32) Ibid., page 94.

33) Drucker, page 28.

34) Ben-Yehuda, pages 111-112.

35) Drucker, page 29.

36) St. John, page 243.

37) Fellman, page 4.

38) St. John, page 87.

39) Ben-Yehuda, page 147.

40) Ibid., page 139.

41) Ibid., pages 146-147.

42) Ibid., page 147.

43) St. John, page 285.

44) Ibid., pages 285 and 287. See also: Fellman, page 3.

45) Ibid., page 288.

46) Ibid., pages 282-283.

47) Ben-Yehuda, pages 114-115.

48) Drucker, pages 56-58; Ben-Yehuda, pages 224-229; and St. John, pages 195-210.

49) St. John, pages 203-204.

50) NSW Board of Jewish Education, “Eliezer Ben-Yehuda,” www.bje.org.au, page 1.

51) Ben-Yehuda, page 265.

52) St. John, page 87.

53) Drucker, page 45.

54) Ben-Yehuda, page 198.

55) Ibid., pages 191-192.

56) Ibid., pages 211-212.

57) Ibid., page 205.

58) St. John, page 284.

59) Ben-Yehuda, pages 315-335.

60) Ibid., pages 306-307.

61) Ibid., page 221.

62) St. John, pages 310-311.

63) Drucker, page 67.

64) Yaffah Berlontz, “Hemda Ben-Yehuda,” Jewish Women’s Archives, www.jwa.org.

65) Drucker, page 71.

66) Ben-Yehuda, page 329.

67) Ibid., page 369.

68) Ibid., pages x-xi.

69) Berlontz, page 29.

70) Jewish Virtual Library, “Academy of the Hebrew Language,” www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

71) Wikipedia, “Hebrew Language,” page 14, www.en.wikipedia.org.

72) Ben-Yehuda, page 219.

73) Jewish Agency for Israel, “Jew! Speak Hebrew!” www.jafi.org, page 2.

74) Ibid., page 3.

75) Ibid.

76) Behadrey Haredim, “Kometz Aleph-Au — How many Hebrew speakers are there in the world?” www.bhol.co.il.

77) Ben-Yehuda, page 373.