Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

The Danger of Forgetting God

Can a virgin forget her ornaments

Or a bride her attire?

Yet My people have forgotten Me

Days without number.

(Jeremiah 2:32)

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn spoke like an Old Testament prophet when he warned America and all the Western world that it was imperiled because it had forgotten God. It proved to be a message that people did not want to hear. Accordingly, Solzhenitsyn died as a prophet without honor.

Solzhenitsyn was a Russian novelist, historian and short story writer who was born in 1918. He was an outspoken critic of the Soviet Union and Communism, and he helped raise global awareness of the inhumanity of the Soviet regime.

Solzhenitsyn grew up in poverty. His father was killed in a hunting accident shortly after his wife’s pregnancy was confirmed. Solzhenitsyn’s mother never remarried. She was an educated woman, and she encouraged her son’s literary and scientific education. She also raised him in the Russian Orthodox faith.

His War Experiences and Arrest

During World War II, Solzhenitsyn served as an officer in the Red Army. He began to develop growing doubts about the moral foundation of the Soviet government when he witnessed repeated war crimes by the Soviet army against German civilians. Elderly people were tortured and looted, and young girls were gang raped to death.

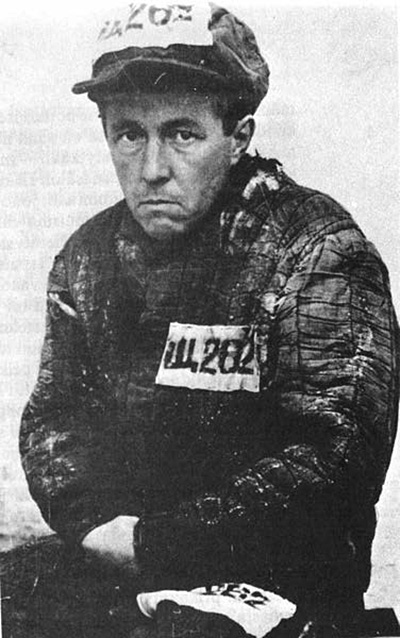

In February of 1945, while serving in East Prussia, Solzhenitsyn was arrested for writing derogatory comments in personal letters about Stalin and his conduct of the war. He was charged with “anti–Soviet propaganda” and was sentenced to an eight year term in a labor camp.

During the next eight years, he was transferred from one forced–labor camp to another throughout what he labeled as “The Gulag Archipelago.” This gave him firsthand observations within the Soviet system for political prisoners. His experiences during this time served as the basis for his novella, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.1

In March of 1953, after his prison sentence ended, Solzhenitsyn was forced into internal exile in northeastern Kazakhstan. He was diagnosed with a cancerous tumor and almost died before the tumor went into remission. It was this experience that served as the basis for his novel, Cancer Ward, which was published in 1968.2

Solzhenitsyn’s terrible experiences in the Gulag convinced him to completely abandon Marxism, and he began to return gradually to his early Christian faith.

The Thawing of Russia

In 1956, Nikita Khrushchev delivered his famous “secret speech” to a closed session of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In the speech, Khrushchev denounced Stalin as a brutal leader and then proceeded to provide a litany of many of his crimes.

This speech launched a period of “de–Stalinization” that included a thaw in the censorship of literature. As a result, Solzhenitsyn was freed from exile. He took a position as a secondary school math teacher and continued his research and writing about the Gulag.

His First Publications

In 1962, at age 44, his short story, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, was published in Novy Mir magazine with the personal approval of Khrushchev who later defended his decision by declaring: “There’s a Stalinist in each of you; there’s even a Stalinist in me. We must root out this evil.”3

The story caused a sensation and was subsequently published in book form. It became an immediate bestseller in both the Soviet Union and the West. It was the only book by Solzhenitsyn to be published in his native country, because after Khrushchev was ousted from power two years later, the censors once again clamped down on anti–Soviet writings. However, between 1962 and 1964, he did publish three short stories in Russian magazines. His next two novels, In The First Circle and Cancer Ward, and a play, The Prisoner and the Camp Hooker, were all published abroad in 1968.4

In 1970, Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. He refused to travel to Stockholm to receive the award because he feared that the Soviet authorities would not allow him to return to Russia. The award cited him “for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature.”5

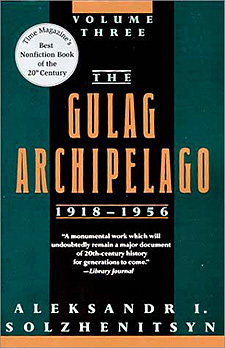

His Historical Blockbuster

Solzhenitsyn’s most famous book, and his tour de force, was The Gulag Archipelago, written between 1958 and 1967 and published in France (in Russian) in 1973. 6 It was a three–volume, seven part detailed historical exposé of the Soviet forced–labor prison system.

The book quickly became one of the most influential publications of the 20th Century. It has since sold over 30 million copies in 35 languages. The book was not published in the Soviet Union but was vehemently attacked by the government controlled press. In the West it was hailed as a masterpiece. George F. Kennan, the influential U.S. diplomat, called the book “the most powerful single indictment of a political regime ever to be levied in modern times.”7

The word, GULAG, in the title of the book is an acronym for the Russian name of the bureaucracy that governed the Soviet labor camp system of prisons. The word, archipelago, was used by Solzhenitsyn to portray this system because the camps were spread across Russia like a vast “chain of islands.”

The publication of this book was the last straw for the Soviet government. In September of 1974, Solzhenitsyn was arrested and deported. In the process, he was stripped of his Soviet citizenship, becoming a stateless person. He went first to Cologne, Germany and then to Zurich, Switzerland. In 1975, Stanford University invited him to move there where he lived on campus before deciding to move to Cavendish, Vermont in 1976. He remained there until 1994 when he returned to Russia.

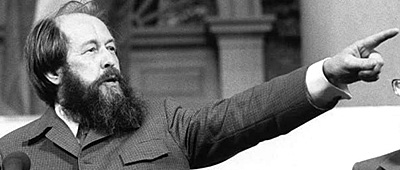

The Speech That Stunned the Western World

Solzhenitsyn’s first public speech in the United States was delivered in June of 1978, three years after his arrival. The occasion was the commencement ceremony at Harvard University where he was granted an honorary degree. He arrived on campus as a hero; he departed as a pariah.

The Harvard intelligentsia was outraged over his presentation, and some actually booed him! The New York Times declared him to be a “dangerous zealot.”8 The Washington Post wrote him off as a man who did not understand Western society.9 Critics denounced him as a “Tsarist reactionary, an Orthodox Christian ayatollah, a hater of democracy [and] a Russian ultranationalist.” 10 None of which were true. As one of his biographers, Daniel J. H. Mahoney, has put it: “Solzhenitsyn wasn’t just dismissed; he was demonized.”11

What in the world had Solzhenitsyn done to provoke such outrage? The answer is simple. He spoke prophetically, and he spoke the truth. And his audience did not want to hear it. So, what did he say?

He began his speech by proclaiming that the Western world, including the United States, had lost its courage in confronting evil. He declared that our foreign policies were based on “weakness and cowardice.” And then he observed: “Should one point out that from ancient times, declining courage has been considered the beginning of the end?”12

Next, he attacked American democracy for its exercise of liberty without self–restraint and for its obsession with solving all problems through its legal system. His words sound like they were spoken yesterday instead of almost 40 years ago:13

The defense of individual rights has reached such extremes as to make society as a whole defenseless against certain individuals… It is time in the West to defend not so much human rights as human obligations.

Destructive and irresponsible freedom has been granted boundless space. Society appears to have little defense against the abyss of human decadence, such as, for example, the misuse of liberty for moral violence against young people [with] motion pictures full of pornography, violence and horror.

Solzhenitsyn’s next target was the press. He criticized it for its lack of “moral responsibility.” He declared the press to be the greatest power within the Western countries, and then he asked, “By what law has it been elected and to whom is it responsible?” 14

He characterized the press as being full of “hastiness and superficiality,” and he argued that the press has a herd mentality which gives birth “to strong mass prejudices” and “blindness.”15

He then shifted his focus to the moral degradation of American society. He pointed to “TV stupor,” “intolerable music,” and “the overall decadence of art.” He decried the lack of “great statesmen.” And he pointed to the thin “surface film” of social stability that can easily be shattered with an electrical blackout that produces looting.16

(https://ethikpolitica.org)

He then posed the crucial question: “How did the West decline from its triumphal march to its present sickness?”17

He answered this question by pointing to what he called “anthropocentricity” — the elevation of Man over God, to the extent that “man [is] seen as the center of everything that exists.”18 In other words, at this point in his speech, Solzhenitsyn began to attack Humanism, the godless philosophy that has become the religion of the Western world.

He proceeded to point out that Humanism always leads to Materialism and Materialism produces “moral poverty.” He made the point powerfully:19

All the glorified technological achievements of Progress, including the conquest of outer space, do not redeem the 20th Century moral poverty which no one could imagine even as late as the 19th Century.

This observation brought Solzhenitsyn to his concluding and defining statement:20

On the way from the Renaissance to our days, we have enriched our experience, but we have lost the concept of a Supreme Complete Entity which used to restrain our passions and our irresponsibility.

We have placed too much hope in political and social reforms, only to find out that we were being deprived of our most precious possession: our spiritual life. In the East, it was destroyed by the dealings and machinations of the ruling party. In the West, commercial interests suffocate it. This is the real crisis.

It was a breathtaking, challenging and stunning presentation. It is no wonder that the negative response to it was so strong. The wonder is that he was not lynched on the spot!

Yet, 33 years later, in 2011, the Harvard Magazine published the speech in full and introduced it with these words that must have outraged Harvard professors: 21

Given the suffering he [Solzhenitsyn] had endured in the Soviet Union, many in the audience expected that the writer’s address would be a stern rebuke to Communist totalitarianism, combined with a paean to Western liberty and democracy. The… audience was in for a rude surprise.

“The Exhausted West,” delivered in Russian with English translation under overcast skies, chastised the arrogance and smugness of Western materialist culture and exposed the adverse effects of some of those achievements that Western democracies had long prided themselves upon…

Solzhenitsyn’s brilliant, iconoclastic speech ranks among the most thoughtful, articulate and challenging addresses ever delivered at a Harvard commencement.

In like manner, Michael Novak, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, has described Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard speech “as the most important religious document of our time.”22

His Greatest Speech

But Solzhenitsyn had an even more powerful and insightful speech he was yet to deliver. It came five years later in May of 1983 when he received the Templeton Prize. This is an award presented by the Templeton Foundation in Pennsylvania. It is an annual award given to a living person who, in the estimation of the judges, “has made an exceptional contribution to affirming life’s spiritual dimension, whether through insight, discovery or practical works.”23

Upon receiving the award at age 65, Solzhenitsyn delivered an address titled, “Godlessness: The First Step Toward the Gulag.”24

He began with a reminiscence from his childhood:25

More than half a century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of older people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.

Then, picking up steam, like a black preacher who gets into a cadence and starts repeating a word or phrase, Solzhenitsyn began to emphasize his point over and over: 26

Since then I have spent well–nigh fifty years working on the history of our [Russian] revolution. In the process I have read hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort to clear away the rubble left by that upheaval.

But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous revolution that swallowed up some sixty–million people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.

Nor did he leave it there. As if he wanted to make certain that his audience was getting the point, he repeated it again:27

What emerges here is a process of universal significance. And if I were called upon to identify briefly the principle trait of the entire 20th Century, here too, I would be unable to find anything more precise and pithy to repeat once again: Men have forgotten God.

February 25, 1974.

He then proceeded to warn that the Western World “is experiencing a drying up of religious consciousness.”28 He said this was happening because “the meaning of life in the West has ceased to be seen as anything more than the ‘pursuit of happiness…'”29

Another problem he identified was the refusal of people to realize the evil that is in the individual human heart and the consequent unwillingness to declare anything as good or evil. The result, he declared, is that the West “is ineluctably slipping toward the abyss.”30

Solzhenitsyn emphasized that we in the West must come to the realization “that human salvation can be found neither in the profusion of material goods nor in merely making money.” Rather, the aim should be “the quest of worthy spiritual growth.” He then asserted that Mankind’s hope can be found only by redirecting our consciousness “in repentance to the Creator of all; without this, no exit will be illumined, and we shall seek it in vain.”31

Putting the same thought in different words, Solzhenitsyn concluded his remarks by urging his listeners to engage in “a determined quest for the warm hand of God, which we have so rashly and self–confidently spurned.”32

His Concluding Years

In 1990 Solzhenitsyn’s Soviet citizenship was restored, and in 1994 he and his wife returned to Russia where they settled near Moscow. He had been married twice and had fathered three sons by his second wife. He died in 2008 of heart failure at the age of 89. He was buried at a monastery in Moscow.

The Bible says that a prophet never finds honor in his own country (Mark 6:4). Nor did Solzhenitsyn in his or in his adopted country. His native country expelled him, and America shut its ears to his fervent warnings and his pleas to return to God. We are now suffering the consequences.

You have forgotten the God of your salvation

And have not remembered the Rock of your refuge.

(Isaiah 17:10)

Notes

1) Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1963).

2) Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Cancer Ward, (New York,NY: Dial Press, 1968).

3) Max Hayward and Edward L. Crowley, eds., Soviet Literature in the Sixties (London: Methuen Books, 1965), page 191.

4) Wikipedia, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aleksandr_Solzhenitsyn, page 11.

5) Official website of the Nobel Prize Foundation, https://www.nobelprize.org/search/?query=1970

6) Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago (Paris, France: Éditions du Seuil , 1973 in Russian). First English publication in 1974 by Harper & Row in New York, NY.

7) The Economist magazine, “Alexander Solzhenitsyn: Speaking truth to power,” April 7, 2008, http://www.economist.com/node/11885318, page 1.

8) David Aikman, “Profiles in Faith: Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Part II: A World Split Apart: Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard Speech Twenty-four Years Later,” www.cslewisinstitute.org, page 1.

9) Ibid.

10) Brian C. Anderson, “Solzhenitsyn’s Permanence,” http://www.newcriterion.comarticles.cfm/Solzhenitsyn-s-permanence-8077, page 1.

11) Ibid.

12) American Rhetoric Online Speech Bank, “Alexandr Solzhenitsyn: ‘A World Split Apart,’ Address at Harvard University on June 8, 1978,” http://americanrhetoric.com/speeches/alexandersolzhenitsynharvard.htm, page 4.

13) Ibid., page 5.

14) Ibid., page 6.

15) Ibid., pages 6-7.

16) Ibid., page 8.

17) Ibid., page 10.

18) Ibid.

19) Ibid., page 11.

20) Ibid., page 12.

21) Unsigned editorial, “Solzhenitsyn Flays the West,” Harvard Magazine, April 25, 2011.

22) David Aikman, page 1.

23) NobelPrize.org, “Lists of Nobel Prizes and Laureates: 1970,” https://www.nobelprize.org/search/?query=1970.

24) Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, “‘Men Have Forgotten God’ — The Templeton Address,” May 1983, http://www.roca. org/OA/36/36h.htm.

25) Ibid., page 1.

26) Ibid.

27) Ibid.

28) Ibid., page 3.

29) Ibid.

30) Ibid.

31) Ibid., pages 3-4.

32) Ibid., page 4.